TW Column by David Biddle

Why the Goddess of Books May Rain on Your Parade

In the fall of 2010, as we drove from Philadelphia to Vermont, my wife and I did the math. Amazon's self-publishing program gave authors 70 percent of net revenues on book sales. That meant you could sell your own e-book for, say, $7.99—two bucks below the standard price set for most e-books produced by the big publishing companies. Amazon got $2.40 per unit sold, and you, the author, got $5.59.

If I could just sell a hundred copies of my book a week, we reasoned, I could make over $25,000 in a year—all without having to kowtow to industry professionals ever again or settling for standard royalty rates below 20 percent.

"It's all about product," I kept saying. "You just need to pound away every day." I was plotting my career. I was going to become a full-time writer. Finally! At 52, I was going to shove my day job of thirty years and write my ass off every single day until I died.

Screw the Man!

Now, the leaves up north are turning bright red again, and I've been an indie author for almost three years. And I haven't made squat—yet. If anything, I feel like the Goddess of Books has been squatting over me on a cruelly random basis, relieving herself as she sees fit. I'm embarrassed to write here that, on average, I make about $10 a month on book sales. That's two to three units sold every four weeks.

It's been painful to lose my original starry-eyed optimism about the book world — especially the e-book world. I don't mean to sound discouraging, but I was stupid to think I could make money quickly in a new industry that's only about five years old. These days, I know how difficult it is to break out as an author, and I'm far less susceptible to the hype of Amazon or any other digital distributor.

So, for all authors who have the same stars in their eyes—who fantasize about making money as a self-published writer just like Hugh Howey or E.L. James but with MUCH better prose—here are three big lessons I've learned.

Lesson 1: There's Way Too Much Competition

My first novel, Beyond the Will of God, originally went on sale in July 2012. As of October 17, 2014, it's ranked by Amazon as #777,029 in the Kindle "Best Sellers" list. The most recent estimate for e-books of all kinds in the Kindle Store is more than 2.9 million books, and by the end of the year, that number will surely be over 3 million.

Not to mince words, but there's a shitload of books out there for sale. This hit home for me about a week after I published my novel. I noticed that the little sidebar Amazon posts on its main Kindle Books page shows the number of releases in the past thirty days. Back then, Amazon's Kindle Store averaged about 50,000 releases a month. Now, it's more than 80,000. In any case, this is the first lesson I had to learn as a self-published writer.

In just the past three months alone, more than 250,000 new releases have popped up on the Kindle system. That's a lot of competition. If you apply the law of supply and demand to this situation, you will feel a serious amount of Goddess pee on your head.

Lesson 2: Literary Fiction Is Still the Ugly Cousin

Despite all the hype about indie lit, self-published literary novels usually do not sell well on Amazon—or anywhere else. All the indie e-book success stories I know involve genre books, especially romance/erotica, mystery/detective, and certain types of science fiction (often young adult steam-punk and dystopian).

This is the "demand" side of the business equation for serious writers. Not a lot of folks buy literary fiction by unknown authors. If you had a choice between my next novel, say, or Paulo Coelho's new book Adultery, which would you purchase—even if mine is selling as an e-book for $4.99 and Coelho's for $7.99?

For any author who's written a genreless, weird book—and who's pounded on the publishing industry gates to no avail—publishing it yourself seems like a no-brainer. You may not have the supposed marketing clout of a corporate investor, but your book's out there. If you're adept at social networking, the sky's the limit.

Except the literary sky does appear to have a limit, at least for now. My unscientific take is that a lot of readers of literary fiction are not yet willing to move their eyeballs to a screen. And the availability of free classic fiction through websites such as Project Gutenberg means that indie authors aren't just competing with several million new publishers; they're up against thousands of road-tested dead greats—from Twain and Shakespeare to Tolstoy and Shelley.

Lesson 3: You Can Drive Yourself Insane Tracking Sales

The third lesson I learned is that publishing books for a living really is what they call a long-tail business. If you're relatively unafraid of social media and putting yourself out there, you can sell a lot of books in the first month after a new release. In fact, I did okay with my novel. I sold about a hundred copies of it in the first two months. Using Amazon's Kindle Direct Publishing system, I also ran a special "free" promotion at the end of the second month and got more than 10,000 downloads.

At first, it was kind of fun checking reports on my account every morning. As far as I know, no traditionally published author has access to real-time sales data. Online book distributors (pretty much all of them) allow self-publishers the awesome luxury of checking the accounting system whenever they want.

However, once sales die down, checking your account is not fun. One evening, about four months after the book's release, my wife found me staring into the infinity of a certain corner in our living room.

"What's wrong?' she asked.

After gulping down some air, I said, "No one's downloaded my book in nearly two weeks. It's depressing. I check every day—and nothing."

"Stop checking," she said.

My wife's amazing. But I still drove myself crazy (and her) for another eight months before I had to admit she was right. I needed to ignore the trickle of monthly numbers and spend my time working on my next project.

The long-tail business idea is important for everyone in the industry. It's the wild card in the supply-and-demand equation. One of the major virtues of digital publishing is that e-books don't go out of print. Beyond the Will of God is available for all time (well, until global warming destroys civilization as we know it). I have two books of short stories for sale as well. And I don't just use Amazon for distribution; my work is available through 22 sites globally.

The beauty of this long-tail game is that the tail extends far beyond anyone's vision of the future. I still believe that if you're a dedicated writer and have a lot of ideas and are willing to learn something new about the craft every day, there's no telling how successful you can be. Right now, I'm working on ten separate book projects. That sounds whacky to some people, but I'll publish each one over the next four or five years. I don't need to wait for an agent or a publisher to give me the nod.

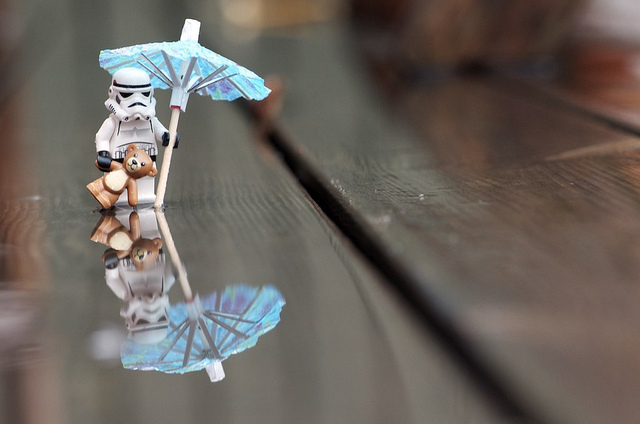

Now, if I could only find an umbrella on Amazon that's big enough.

Art Information

- “Rain Vain” © Román P. G.; Creative Commons license.

- “Umbrella: On a Rainy Day in Salzburg” © Thomas Geiregger; Creative Commons license.

- “Share Alike” © Kristina Alexanderson: Creative Commons license.

David Biddle is TW's "Talking Indie" columnist. He's the author of the novel Beyond the Will of God as well as several collections of short stories. As a freelance writer, David has published articles and essays in everything from Harvard Business Review, Huffington Post, and the Philadelphia Inquirer to Kotori Magazine, InBusiness, and BioCycle.

For information about his novel and other writing, see David Biddle's website.

David notes that Kindle e-book publishing statistics change constantly. To track them in real time, check the left sidebar in Amazon's Kindle Store.