Theme Essay by Jeremiah Horrigan

Undoing the Damage of the Online Rant

When it comes to hypocrisy, I’ve found there’s no better place to experience it firsthand than on the Internet.

The online opportunities for hypocritical behavior—defined by Webster’s as “the false assumption of an appearance of virtue”—are as endless as the number of stories and comments you read, post, or respond to every day.

The online opportunities for hypocritical behavior—defined by Webster’s as “the false assumption of an appearance of virtue”—are as endless as the number of stories and comments you read, post, or respond to every day.

It’s easy to spot hypocrisy in others, not so easy to spot it in oneself. To be confronted by one’s own posturing is to be presented with an ominously ticking package, delivered unbidden by a stranger whom you know doesn’t really have your best interests in mind. Just as you know exactly what will happen if you dare unwrap or—God help you—open such a package.

Special delivery? No, thanks. Return to sender.

But sometimes the postman rings more than twice.

• • •

I begin my story with a description of how I see myself:

I’m a civilized person and never more civilized than when I write. I’m considerate of others. I don’t rant. I discuss. I carefully weigh my opinions before I present them. And when I voice them, I don’t use insulting or childish language to make my points. Yes, I’m above all that—although, in all candor, I’m not above lecturing others (temperately, cleverly) when they fail to meet the standards I’ve set for myself. But whenever I’ve done that, I’ve been the very soul of consideration, ever careful not to tread on anyone’s feelings.

So, there I was in my basement redoubt some months ago, civilized as always, idly tooling around the Internet. As it happened, I was drawn to a headline at Salon, one of my favorite cyberports of entry. I read the accompanying story. I thought the headline promised one thing and the story delivered another. I felt I’d been snookered. Sold a bill of goods.

The writer—and what he’d written—had wasted a precious five minutes of my life. This was not right. I couldn’t let such balderdash pass unremarked.

So I wrote a clever comment and posted it. I was righteous in my indignation. I backed up my statements with fact. It didn’t take more than ten minutes to write and post. I forgot about it almost as soon as it went up.

The next day, I noticed that the author of the post had responded to my comment. He didn’t call me out, didn’t question my professionalism the way I’d questioned his. In measured, reasonable words, he simply let me know I’d hurt him with my comment.

He called my comment mean-spirited.

I blushed the moment I read those words. I knew he was right. My clever riposte had been nothing more than a sour diatribe, a chance to unload some free-floating anger in his direction.

So I did what any newly exposed hypocrite would do: I set about trying to make things right. I got the guy’s e-mail address, eager to apologize. But, even though I was sincere in acknowledging his complaint, even as I wrote my apology, I knew he wasn’t the primary target of my effort. I didn’t just want to repair the damage I’d done to him. I wanted even more urgently to repair the damage I’d done to my image of myself.

I got in touch with the author, and he accepted my apology gracefully. We exchanged a few more e-mails after we found we’d covered some similar stories for other publications. Then we lost track of each other.

That might have been the end of the story, except something continued to nag at me. I’d convinced my victim of my regret, but I hadn’t convinced myself. I knew at some level that I’d been given a glimpse of something that went deeper, something I was at once familiar with but didn’t want to examine closely—or at all.

I needed to take a fuller accounting of what I’d done, to stare a bit at the gap between the way I thought of myself and the way I’d actually behaved. I’d acted the lout, without a second thought. The alacrity with which I’d behaved suggested that this was nothing new for me, that I was pretty good at it. I didn’t like that thought, but neither could I deny it.

I’ve since found a description of what I felt—and why the incident kept nagging at me—in a passage by Jungian astrologer Liz Greene, in her book Barriers and Boundaries: The Horoscope and the Defences of the Personality.

Turns out I wasn’t simply feeling guilty for being caught out in a hypocritical act, as I first suspected; I was feeling remorse for my act. Greene writes:

“When we feel remorse, we feel deeply ashamed of what we are or have done. This shame and desire to atone arise from the instinctive knowledge of how it feels to be the person we have injured. There is no escape from the stark humiliation and humility of remorse.

Remorse, she writes, can be transformative:

It has the power to ensure that we never repeat the destructive action again.

Since that episode, I’ve read any number of posts or comments in my daily cyber-travels that I’ve found indefensible, unfair, plain wrong, or insulting to people I respect. And, in the heat of those feelings, I’ve written any number of scabrous “responses.” They have been clever, to the point. Some of them contained the bonniest mots I’ve ever written. And they all seemed—at the time of their writing—the very soul of civility.

But I’ve come to distrust my ability to judge myself in the heat of anger. I no longer end my comment-writing with the quick stab at the “Submit” button that embodied the righteous satisfaction I took in delivering my Salon riposte. Against my every wish and inclination, I’ve ended instead by stashing each one and waiting at least 24 hours before rereading it.

But I’ve come to distrust my ability to judge myself in the heat of anger. I no longer end my comment-writing with the quick stab at the “Submit” button that embodied the righteous satisfaction I took in delivering my Salon riposte. Against my every wish and inclination, I’ve ended instead by stashing each one and waiting at least 24 hours before rereading it.

And, in most cases, a day’s passage has done what time does so well—provided perspective. It’s allowed the passion to cool and my true motivations to bob to the surface like the gas bubbles they usually are.

I know, I know. I said “in most cases.” A few of my comments have either withstood the 24-hour test or escaped their limbo prematurely. My hoped-for transformation has been incomplete. Call it a failure of imagination, call it backsliding, but in the few cases where I let my outrage loose unmediated by time in the cooler, I’ve not regretted it.

Yet.

Here’s the point: When the Salon writer made his pain evident to me, I was struck by lightning. It happened when my guard was down, while I was busy doing other things. And for no reason I can claim as my own, I was given the grace to linger with the knowledge of what I’d done and see it for what it was.

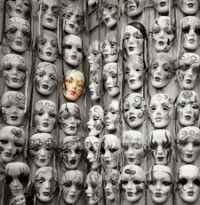

Luckily for me, that bolt from the blue provided exactly enough illumination to glimpse the self-image I so rarely see or even want to see. In that moment, I saw the mask I spend so much of my time crafting and hiding behind, especially here on the Internet. And for that brief glimpse, for the shock it caused me and the changes it wrought, I’m grateful.

Publishing Information

- Liz Greene, Barriers and Boundaries: The Horoscope and the Defences of the Personality (London: CPA Press, 1998).

Art Information

- “Masks” © Brian Snelson; Creative Commons license

- “Maschera di Carnevale” © gnuckx; Creative Commons license

- “#166 Mask” © Caroline; Creative Commons license

Jeremiah Horrigan is a contributing writer at Talking Writing and a lifelong newspaper reporter.

Jeremiah Horrigan is a contributing writer at Talking Writing and a lifelong newspaper reporter.

“My training in the Five Ws had prepared me for a lot, but not for this: a melancholy parade of desperate people, trapped overnight in a broken-down, memory-haunted, Borscht Belt palace." — "The Editor Inside Me"