Editor's Note by Martha Nichols

Learning to Be Your Own Gatekeeper

Whenever anyone asks me the dreaded question—Hey, how's the novel going?—admitting to rejection feels like I've done a pratfall in the middle of an airport.

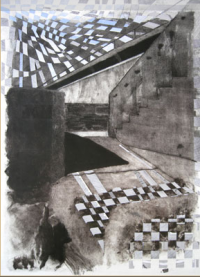

There's no dignity in rejection. Suffering for its own sake? Forget it. I’m far from the first to call rejection a dirty word. For eons, the hurdles faced by writers without money to publish their own work or access to those who control the presses have been too high. In this issue of Talking Writing, we've gathered many evocative images of gates and walls and deserted roads to make the point.

There's no dignity in rejection. Suffering for its own sake? Forget it. I’m far from the first to call rejection a dirty word. For eons, the hurdles faced by writers without money to publish their own work or access to those who control the presses have been too high. In this issue of Talking Writing, we've gathered many evocative images of gates and walls and deserted roads to make the point.

Yet, like most magazine editors, I've been on both sides of the gate. After plenty of pratfalls—four novels and counting moldering in my file drawers—the editor in me also knows that some of those manuscripts aren't publishable. They were practice. They were great raw material that never gelled. At least one could have succeeded if I and my agent (or another agent) had kept pushing, but I didn't push. I gave up too soon, and that in itself is an important lesson for anyone in publishing.

I've come to see rejection as a necessary part of my writing process. Sometimes there's no way for the most talented young authors to realize they’re offtrack unless a critic points it out—be that critic a parent, a teacher, a fellow writer, or an editor.

It's a huge irony, of course: To get noticed, you need a distinctive voice; yet to connect with an audience, you must write about more than yourself. Good writing is like a circus act, an elephant balancing on a tightrope. It requires control, but not too much, and it's very hard to do without feedback.

That’s why gatekeeping can be useful, especially for those of us in this for the long haul. I'm not talking about rejections that send a creative person into hiding—that's never helpful. I mean gatekeeping that saves authors from themselves. In the heat of the writing moment, all of us can sweat the wrong kind of bullets (believe me, I know), because this sentence is Exhibit A.

That’s why gatekeeping can be useful, especially for those of us in this for the long haul. I'm not talking about rejections that send a creative person into hiding—that's never helpful. I mean gatekeeping that saves authors from themselves. In the heat of the writing moment, all of us can sweat the wrong kind of bullets (believe me, I know), because this sentence is Exhibit A.

Readers benefit from gatekeeping most of all. But as the new media landscape evolves through blogging and online news sites, too many writers dismiss editorial standards as if they’re the equivalent of censorship. Now we’re awash in the sloppy prose and false claims that would make William Strunk and E.B. White spin in their graves.

(I’m not the first to employ that cliché, either. Just Google “Strunk and White spinning in their graves” and see what pops up.)

Student journalists often don't check whether what they’ve written has been said before or is even true. It’s as if everything is happening at the moment of writing, a stream-of-conscious self-absorption that trumps originality or the past.

I believe good research skills can be taught—and need to be taught—but what's really up for grabs now is who makes the judgment call about “good” writing.

In the Jan/Feb 2012 issue of TW, we explore gatekeeping and quality control in a publishing industry that’s redefining quality even as I type. It's not just a question of who gets to decide; it's a question of which gatekeepers still matter. Editors? Journalists? Literary agents? Twitter aficionados? Amazon?

Several TW writers look at the current odds against having an unsolicited manuscript accepted by an agent or a magazine. In “My Stint as a Literary Doorman,” David Cameron chronicles the year he spent as a slush pile reader for Tin House, overwhelmed by stories in his Submishmash queue.

On the glossy magazine side, Lynya Floyd, health director at Family Circle, argues that “Editors Read Your Pitches—Really,” offering tips for how to get an editor’s attention. And in “Why Reader Taste Differs from Publisher Taste,” literary agent Jenny Bent admits her glee at the rise of self-publishing and the trouncing of “East Coast” standards.

Meanwhile, David Biddle examines the hoopla surrounding Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding in “Harbach and the Hard Sell,” noting that this baseball novel’s publishing story is just as interesting as the book itself.

Meanwhile, David Biddle examines the hoopla surrounding Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding in “Harbach and the Hard Sell,” noting that this baseball novel’s publishing story is just as interesting as the book itself.

In addition to provocative theme essays, January and February at Talking Writing feature math poetry—a genre that may seem forbidding at first glance. But we’re excited about how these unusual poems use math concepts such as group theory to find meaning in the world around us. Poetry Editor Carol Dorf introduces the series in “Why Poets Sometimes Think in Numbers." And Executive Editor Elizabeth Langosy adds a humorous note about attending a recent math poetry reading in Boston in "A Nonmathematician Falls in Love."

Magazine gatekeeping isn’t just about saying no, after all. It’s about framing material for readers in fresh ways. The various tricks we use, like kicky blurbs and headlines, are about drawing readers to TW—of course. But we also want to attract bigger audiences to writing that deserves a spotlight.

In this issue, we present “Escape from Frog Island,” a chapter of Fred Setterberg’s Lunch Bucket Paradise (Heyday, 2011). In his companion essay, “What’s a True-Life Novel?,” Fred recounts what compelled him to convert his original memoir manuscript into the transcendent fiction of the published book.

Ultimately, the most important gatekeeper is yourself. This gatekeeper can take on many guises: Fred’s fear of an Oprah interrogation, even the Jack Webb character Jeremiah Horrigan describes in “The Editor Inside Me.” Sometimes a writer’s inner hard-ass is another roadblock. Still, most of us absorb the good advice we receive from colleagues and other trusted readers. And we learn from external gatekeepers like newspaper editors and agents, those who care enough to be honest with us.

As an editor, I really do care about the quality of a writer’s work. I care because, in an online world in which readers are overwhelmed by information, conveying complicated ideas in an engaging way matters more than ever. I care because I love journalism and literature—and I’m determined to nudge and spark and shake TW writers into illuminating what they observe with sharp analysis.

I mourn the recent passing of Christopher Hitchens for many reasons, but especially because “his prose rocked and rolled in face of the demure, the hypocritical, and the ignorantly self-important,” as Simon Schama writes in his Newsweek memorial:

The vacancy will be especially felt on the American side of the ocean, where, as one of Hitch’s heroes (George Orwell) put it, ‘in our time political speech and writing is largely the defense of the indefensible’ contaminated by ‘flyblown metaphors.’ Anyone, Hitchens thought, who spoke with stale laziness of ‘kicking the can down the road’ should themselves receive the end of the boot.

A little bit of that boot has done me good; I wouldn’t be here if it hadn’t. Authors down the ages have lauded the one insightful critic who has inspired them as well as reined in their worst impulses. For me, it’s not just one. My writing-group peers, tough-love editors, professors, at least one agent, my favorite authors, my father, my TW colleagues, and my own inner hard-ass have all shaped who I am as a writer, pratfalls included.

Is rejection easy to shrug off? Nope. But if you find yourself cursing the unfairness of it all, stop to consider why you think publishing should be a snap. Think of the writers you love—the best writers—all those tightrope-walking elephants, somehow dancing in air.

Table of Contents for the Jan/Feb 2012 Issue

Publishing Information

- “How Hitchens Said Goodbye” by Simon Schama, Newsweek, December 26, 2011/January 2, 2012 (double issue).

Art Information

- Stairway No. 1″ © Susan Denniston; Used with Permission

- “Chaos of Security” © Susan Denniston; Used with Permission

- “Secrets Returned to the Sea” © Susan Denniston; Used with Permission

Martha Nichols is editor in chief of Talking Writing.

As Martha heads off with her family for a brief sabbatical in Asia, she'll be dusting off her latest novel, reworking it, hoping she gets it right—or finds the time and courage to self-publish it.

"The irony of writing about music you love is that it’s like trying to trap smoke in a bottle. Pop music, in particular, gets its hooks into young psyches, providing the sound track for first kisses, first rebellions, first…well, everything that means anything." — "Don't Take Away My David Bowie"