TW Column by Martha Nichols

On Avoiding Lena Dunham Syndrome

I’ve always been an impatient reader. Way back in seventh grade, I searched the La Vista Junior High School library shelves with one goal in mind: a first-person narrator.

I loved stories told by the characters themselves. I relied on them to take me away from the strip malls of Hayward, California. In the early 1970s, I decked myself in orange tie-dyed pants. I wore granny glasses, parting my hair in the middle, a dead ringer for John Lennon. I can’t pinpoint exactly when I picked up, say, The White Mountains. But I know I found John Christopher’s science fiction series in that library. I remember sunlight streaming through utilitarian windows, turning pages, hitting the first-person jackpot: The clockman had visited us the week before, and I had been permitted for a time to look on while he cleaned and oiled the Watch....

As a teenager, I would have said “I” stories were easier reads. Decades later, the adult-me, the magazine writer and editor, says first-person stories feel more real.

I’ve never lost my love of first-person narrators, but the difference now is that I’m hooked by first-person journalism. This semester, I’m even teaching a journalism course with that title, using Joan Didion’s The White Album as one of the main texts. Her personal reportage of the ‘60s and ‘70s has greatly influenced my own attitude toward nonfiction: I don't believe a third-person POV is inherently more objective, and the bias of a first-person account is often what makes it ring true.

“I had better tell you where I am, and why,” Didion says at the start of her essay “In the Islands.” Within the first paragraph, she reveals she’s in Honolulu with her husband and three-year-old daughter, waiting for news of a possible tidal wave. Then:

We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for a divorce. I tell you this not as aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind.

These days, first-person journalism like this is not new. Columns, advice articles, and personal essays by everyone from Didion and Hunter S. Thompson to M.F.K Fisher and John McPhee have long appeared in magazines and newspapers. But with the rise of blogging and the Web, use of the “I” voice is now changing the traditionally omniscient stance of many journalistic features.

Bravo—except there's also a downside to the trend of talking about everything that's ever happened to you ever. Such "aimless revelation," in Didion's tart words, gives personal preoccupations the same weight as universal problems.

First-person journalists acknowledge their biases up front, identifying who’s behind the “I.” More important, though, they link their own stories to larger themes. Didion’s “In the Islands” moves from her personal situation to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel’s privileged history to the Punchbowl—a U.S. military cemetery on Oahu, where she observed graves being dug for American soldiers killed in Vietnam.

First-person journalism helps restrain the pull of TMI when narrating your own life, and it’s my antidote to much of what goes on in creative nonfiction classes. I’m tired of the hothouse quality of many memoirs, especially those in which writers imply "if I remember it this way, it must be true." At worst, revealing private experiences in a public forum invites a nasty kind of voyeurism.

First-person journalism helps restrain the pull of TMI when narrating your own life, and it’s my antidote to much of what goes on in creative nonfiction classes. I’m tired of the hothouse quality of many memoirs, especially those in which writers imply "if I remember it this way, it must be true." At worst, revealing private experiences in a public forum invites a nasty kind of voyeurism.

Exhibit A: Lena Dunham. Early this November, right-wing commentators accused the star of HBO’s Girls of sexually “abusing” her baby sister, based on scenes from Dunham’s 2014 essay collection Not That Kind of Girl. In one passage, written from the perspective of her seven-year-old self, Dunham describes her childish curiosity about female anatomy getting “the best of me”:

Grace was sitting up, babbling and smiling, and I leaned down between her legs and carefully spread open her vagina. She didn’t resist, and when I saw what was inside I shrieked.

It turns out that baby Grace had stuck some pebbles inside herself.

In another scene, Dunham claims she often bribed her little sister for “her time and affection.” Innocent as this is, the offhand comic tone of the following passage is what got Dunham into trouble. She riffs about what she would give Grace:

Three pieces of candy if I could kiss her on the lips for five seconds. Whatever she wanted to watch on TV if she would just ‘relax on me.’ Basically, anything a sexual predator might do to woo a small suburban girl I was trying.

The sex-abuse story went viral, picked up by People, ABC News, and other mainstream outlets. Online sites funded by conservative think tanks trumpeted the headlines as if they were a matter of fact, not opinion. After a series of angry tweets—I told a story about being a weird 7 year old. I bet you have some too, old men, that I'd rather not hear—Dunham has ended up apologizing for those parts of the book.

At this point, she has supporters and detractors of every political stripe. The problem is, Dunham is a celebrity, and her essays often feel like information dumps meant to massage her image. She’s a satirical exaggerator and admits to altering some facts. That’s a common practice by memoirists and humorists such as David Sedaris. Yet, the controversy over her essays is not about fact checking, but her point of view.

A wiser first-person voice would have avoided “sexual predator,” a loaded term for many readers. (Never mind that opening her sister’s vagina strains credulity.) That voice might have pondered what Grace thinks about having her body described like this. Dunham’s sister has supported her account of what happened, but in a New York Times Magazine profile earlier this fall, Grace is quoted as saying “most of our fights have revolved around my feeling like Lena took her approach to her own personal life and made my personal life her property.”

A wiser first-person voice would have avoided “sexual predator,” a loaded term for many readers. (Never mind that opening her sister’s vagina strains credulity.) That voice might have pondered what Grace thinks about having her body described like this. Dunham’s sister has supported her account of what happened, but in a New York Times Magazine profile earlier this fall, Grace is quoted as saying “most of our fights have revolved around my feeling like Lena took her approach to her own personal life and made my personal life her property.”

Dunham is often lauded (or trounced on) for examining every detail of her existence. In fact, little in Not That Kind of Girl examines why the details matter. I'm not offended by lines like "I've always known there was something wrong with my uterus," but they don't open new emotional vistas, either. When personal essays lack what Phillip Lopate calls the “intelligent narrator," the candor becomes eye-glazing—the aimless revelation of a media star known for her exhibitionism.

The value of a first-person journalism perspective, then, has as much to do with a writing approach as the final product. If you think your job is to talk about more than yourself, then the whole process—from conceptualizing the idea to doing research to interpreting what you discover—becomes richer, deeper, and more self-critical.

Consider Mary Beard. Almost fifteen years ago in the London Review of Books, the British classics professor recounted being raped as a young woman. In that piece, titled “Diary,” she minces no words: “In September 1978, on a night train from Milan, I was forced to have sex with an architect.” More to the point of first-person journalism, she goes on to connect this anecdote to a larger theme:

What I am trying to highlight is the crucial importance, both culturally and personally, of rape-narratives. For rape is always a (contested) story, as well as an event; and it is in the telling of rape-as-story, in its different versions, its shifting nuances, that cultures have always debated most intensely some of the unfathomable conflicts of sexual relations and sexual identity.

Beard is colorful and outspoken, but she’s a gray-haired academic. Dunham is a hipster celebrity in her twenties, and she isn’t writing for the intellectual elite (even if the New Yorker publishes her on occasion). Yet, Dunham is writing for other young feminists, and that’s where her use of “I” seems so unexamined. She and other writers of her generation assume the act of writing it all down provides catharsis and a new kind of openness—that telling a personal story is enough.

Feminist though I am, I don’t believe the personal is inevitably political. Nor is it a sufficient explanation for why readers should care. I want interpretation, critical thinking, and a bigger view of the world than the interior of somebody’s head. Journalists, for all their flaws, are trained to provide the who-what-where-when specifics of their observations. In a first-person feature, they make clear who the “I” is and why “I” is telling the story. And they approach information sources with necessary skepticism, whether it’s a politician, Mother Teresa, or themselves.

The most powerful essay in Not That Kind of Girl is the one where Dunham admits, “I’m an unreliable narrator.” In that essay (“Barry”), she focuses on a date-rape incident in college, and the fact that she has struggled with remembering or explaining what happened feels authentic:

I’ve told the story to myself in different variations—there are a few versions of it rattling around in my memory, even though the nature of events is that they only happen once and in one way. The day after, every detail was crisp (or as crisp as anything can be when the act was committed in a haze of warm beer, Xanax bits, and poorly administered cocaine).

Here, Dunham is a first-person narrator I believe in. Like Beard, she details the ways she constructed and revised her rape story, and the toll this has taken on her.

That’s why I have faith in first-person journalism. I see its potential to illuminate complex issues amid the digital swamp of aimless revelation we're now awash in. All writers’ observations are influenced by their identities and circumstances. When the “I’ voice really conveys who an author is, it’s not just another piece of banal content circulating around the Web. It’s been given meaning by somebody.

From this column, you know the following about me: I grew up in California; I was a bookworm who felt awkward as a teen; I’m white; I like science fiction; I’m now in my fifties; I teach journalism; I’m a feminist; I’m a contrarian; I love personal stories; I love facts; I’m biased, far more biased than a journalist is supposed to be.

Does it matter that you know all this? Oh, I think it does.

Publishing Information

- The White Mountains by John Christopher, originally published in 1967 (reissued as Book 1 of the “Tripods” series by Aladdin/Simon and Schuster, 2010).

- “In the Islands” by Joan Didion from The White Album, originally published in 1979 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009).

- Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She’s “Learned” by Lena Dunham (Random House, 2014).

- “Lena Dunham Apologizes for ‘Sexual Predator' Section in Her Book” by Michael Rothman, Good Morning America, ABC News, November 4, 2014.

- “Lena Dunham Is Not Done Confessing” by Meghan Daum, New York Times Magazine, September 10, 2014.

- “Reflection and Retrospection: A Pedagogic Mystery Story” by Phillip Lopate in To Show and to Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

- “Diary” by Mary Beard, London Review of Books, August 24, 2000.

Art Information

- “Ugh. I Don’t Know. I Just Don’t Know” © Deborah Austin; Creative Commons license.

- “It’s All About Me” © Arthur; Creative Commons license.

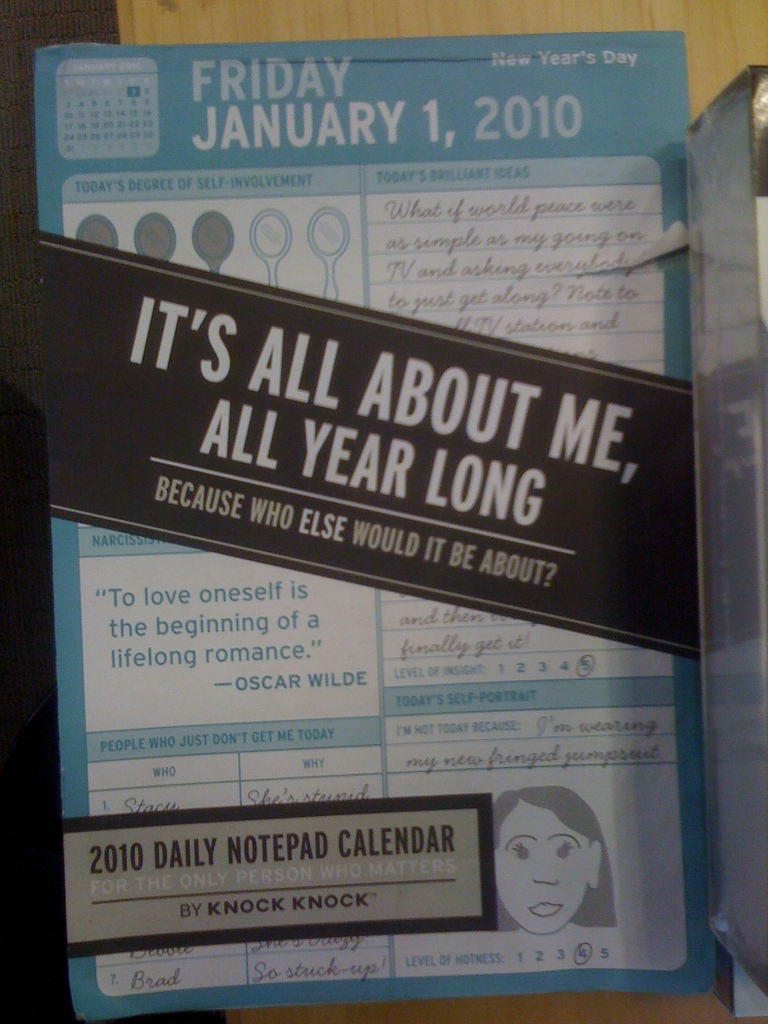

- “Because It’s All About Me” © Raul Pacheco-Vega; Creative Commons license.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing. She teaches journalism at the Harvard University Extension School.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing. She teaches journalism at the Harvard University Extension School.

Memoir writers have a lot to teach journalists, too, Martha notes. Still, she loves this passage from To Show and to Tell by Phillip Lopate: "Sooner or later...you have chewed up the tastiest limbs of your life story, and research becomes an alternative to further self-cannibalization."