Short Story by Andrew Lam

The day after Mama and Papa took off to Las Vegas, Grandma died. Lea and me, we didn’t know what to do. Vietnamese traditional funerals with incense sticks and chanting Buddhist monks were not our thing.

“We have a big freezer,” Lea said. “Why don’t we freeze Grandma? Really, why bother Mama and Papa—what’s another day or two for Grandma now anyway?”

Since Lea’s older than me and since I didn’t have any better idea, we iced Grandma.

Grandma was ninety-four years, eight months, and six days old when she died. She had seen lots of things and lived through three wars and two famines. She lived a full hard life, if you ask me. America, besides, was not all that good for her. She had been confined to the second floor of our big Victorian home as her health was failing, and she did not speak English and only a little French. French like “Oui, monsieur, c’est evidemment un petit monstre.” And “Non, Madame, vous n’êtes pas du tout enceinte, je vous assure.” She was a head nurse in the maternity ward of the Hanoi hospital during the French colonial time. I used to love her stories about delivering all these strange two-headed babies and the Siamese triplets connected at the hip whom she named Happy, Liberation, and Day.

Grandma died a quiet death really. She was eating spring rolls with me and Lea. Lea was wearing this real nice black miniskirt and her lips were painted red and Grandma said, “You look like a high-class whore.” And Lea made a face and said she was preparing to go to one of her famous San Francisco artsy-fartsy cocktail parties where waiters are better dressed than most Vietnamese men of high-class status back home and the foods are served on silver trays and there is baby corn, duck paté, salmon mousse, and ice sculptures with wings, and live musicians playing Vivaldi music. “So eat, Grandma, and get off my case, because I’m no whore.”

“It was a compliment,” Grandma said, winking at me, “but I guess it’s wasted on you, child.” Then Grandma laughed, her breath hoarse and thinning, her deep wrinkled face a blur. Still, she managed to say this much as Lea prepared to leave: “Child, do the cha-cha-cha for me. I didn’t get to do much when I was young, with my clubbed foot and the wars and everything else.”

“Sure, Grandma,” Lea said and rolled her pretty eyes toward the chandelier. Then Grandma just dropped her chopsticks on the hardwood floor—clack, clack, clatter, clack, clack—leaned back, closed her eyes, and stopped breathing. Just like that.

So we iced her. She was small enough that she fit right above the TV dinner trays and the frozen yogurt bars we were going to have for dessert. We wrapped all of grandma’s five-foot-three, ninety-eight-pound lithe body in Saran wrap and kept her there and hoped Mama and Papa would get the Mama-Papa-come-home-quick-Grandma’s-dead letter that we sent to Circus Circus, where they were staying, celebrating their thirty-third wedding anniversary. In the meanwhile, Lea’s got a party to go to and I’ve got to meet Kayden for a movie.

It was a bad movie, too, if you want to know the truth. But Kayden is cool. Kayden has always been cool. Kayden’s got eyes so green they make you want to become an environmentalist. Kayden’s got this laugh that makes you warm all over. And Kayden is really beautiful and a year older than me, a senior. The movie is called Dragon, starring this Hawaiian guy who played Bruce Lee. He moaned and groaned and fought a lot in the movie, but it just wasn’t the same. Bruce Lee is dead. Bruce Lee could not be revived even if the guy who played him had all these muscles to crack walnuts and lay bricks with. Now Grandma was dead, too.

So Kayden and I got home and necked on the couch. Kayden liked Grandma. Grandma liked Kayden. Though they hardly ever spoke to one another because neither one knew the other’s language, there was this thing between them, you know, mutual respect, like one cool old chick to one cool young dude thing. (Sometimes I would translate, but not always ‘cuz my English is not all that good and my Vietnamese sucks.)

What’s so cool about Grandma is that she’s the only one who knows I’m bisexual. I mean, I hate the term, but I’m bisexual, I suppose, by default ‘cuz I don’t have a preference and I respond to all stimuli and Kayden stimulated me at the moment, and Grandma, who for some reason, though Confucian born and trained, and a Buddhist and all, was really cool about it. One night, I remember, we were sitting in the living room watching a John Wayne movie together and Kayden was there with me and Grandma while Mama and Papa had just gone to bed. (Lea was again at some weird black-and-white ball or something like that.) And Kayden leaned over and kissed me on the lips, and Grandma said, “That’s real nice,” and I translated and we all laughed and John Wayne shot dead five mean old guys. Just like that. But Grandma didn’t mind, really. She’d seen Americans like John Wayne shooting her people before and always thought John Wayne was a bad guy in the movies and she’d seen us more passionate than a kiss on the lips and didn’t mind. She used to tell us to be careful and not make babies—obviously a joke—‘cuz she’s done delivering them. She also thought John Wayne was uglier than a water buffalo’s ass, but never-you-mind. So, you see, we liked Grandma a lot.

Now Grandma’s packed in 20-degree Fahrenheit. And the movie sucked. On the couch in the living room after awhile I said, “Kayden, I have to tell you something.”

“What?” asked Kayden.

“Grandma’s dead,” I said.

“You’re kidding me!” Kayden whispered, showing his beautiful white teeth.

“I kid you not,” I said. “She’s dead, and Lea and me, we iced her.”

“Shit!” said Kayden. “Why?”

“‘Cuz she would start to smell otherwise, duh, and we have to wait for my parents to perform a traditional Vietnamese funeral.” We fell silent for awhile then, holding each other. Then Kayden said, “Can I take a peek at Grandma?”

“Sure,” I said, “sure you can; she was just as much yours as she was mine,” and we went to the freezer and looked in.

The weird thing was the freezer was on defrost and Grandma was nowhere in sight. There was a trail of water and Saran wrap leading from the freezer to her bedroom, though, so we followed it. On the bed, all wet and everything, there sat Grandma counting her Buddhist rosary and chanting her diamond sutra. What’s weirder still is that she looked real young. I mean around fifty-four now, not ninety-four. The high cheekbones had come back, the rosy lips. When she saw us, she smiled and said, “What do you say we all go to one of those famous cocktail parties that Lea’s gone to, the three of us?”

Now, I wasn’t scared, she being my Grandma and all, but what really got me feeling all these goosebumps on my neck and arms was that she said it in English, I mean accentless California English. I mean the way Mrs. Collier, our neighbor, the English teacher, speaks English. Me, I have a slight accent still, but Grandma’s was like that of an announcer on NPR.

“Wow, Grandma,” said Kayden, “your English is excellent.”

“I know,” Grandma said, “that’s just a side benefit of being reborn. But enough with compliments; we’ve got to party.”

“Cool,” said Kayden.

“Cool,” I said, though I was a little jealous ‘cuz I had to go through junior high and high school and all those damn ESL classes and everything to learn the same language while Grandma just got it down cold—no pun intended—‘cuz she was reborn. And Grandma put on this nice brocade red blouse and black silk pants and sequined velvet shoes and fixed her hair real nice and we drove off downtown.

Boy, you should’ve seen Lea’s face when we came in. I mean she nearly tripped over herself and had to put her face on the wing of this ice sculpture that looked like a big melting duck to calm herself. Then she walked straight up to us, all haughty like, and said, “It’s invitation only, how’d y’all get in?”

“Calm yourself, child,” said Grandma. “I told them that I was a board member of the Cancer Society and flashed my jade bracelet and diamond ring and gave the man a forty-dollar tip.” And Lea had the same reaction Kayden and I had: “Grandma, your English is flawless!” But Grandma was oblivious to compliments. She went straight to the punch bowl to scoop up some spirits, and that’s when I noticed that her clubbed foot was cured and she had this elegant grace about her. She drifted, you might say, across the room, her hair floating like gray-black clouds behind her, and everyone stared, mesmerized.

Needless to say, Grandma was the big hit at that artsy-fartsy party. She had so many interesting stories to tell. The feminists, it seemed, loved her the most. They crowded around her like hens around a barnyard rooster and made it hard for the rest of us to hear. But Grandma told her stories all right. She told them how she’d been married early and had eight children while being the matriarch of a middle-class family during the Viet Minh Uprising. She told them about my grandfather, a brilliant man who was well-versed in Moliere and Shakespeare and who was an accomplished violinist but who drank himself to death because he was helpless against the colonial powers of the French. She told everyone how single-handedly she had raised her children after his death and they all became doctors and lawyers and pilots and famous composers.

Then she started telling them how the twenty-four-year-old civil war divided her family up and brothers fought brothers over some stupid ideological notions that proved terribly bloody but pointless afterward. Then she told them about our journey across the Pacific Ocean in this crowded fishing boat where thirst and starvation nearly did us all in, but we survived to catch glimpses of this beautiful America and become Americans.

She started telling them, too, about the fate of Vietnamese women who must marry and see their husbands and sons go to war and never come back. Then she recited poems and told fairy tales with sad endings, fairy tales she herself had learned as a child, the kind she used to tell my cousins and me when we were real young. There was this princess, you see, who fell in love with a fisherman, and he didn’t know about her ‘cuz she only heard his beautiful voice singing from a distance, and so when he drifted down river one day, she died, her heart turning into this ruby with the image of his boat imprinted on it. There was also this faithful wife who held her baby waiting for her war-faring husband every night on a cliff, and one stormy night, out of pity, the gods turned her and her child into stone. In Grandma’s stories, the husbands and fishermen always come home, but they come home always too late and there was nothing they could do but mourn and grieve.

Grandma’s voice was sad and seductive and words came pouring out of her like rain, and the whole place turned quiet, and Lea sobbed because she understood. Kayden, he stood close to me, put a hand on my shoulder and squeezed slightly, and I leaned against him and cried a little, too.

“I lost four of my children,” Grandma said, “twelve of my grandchildren and countless relatives and friends to wars and famines, and I lost everything I owned when I left my beautiful country behind. Mine is a story of suffering and sorrow, sorrow and suffering being the way of Vietnamese life. But now I have a second chance and I am not who I was, and yet I have all the memories, so wherever I go, I figure, I will keep telling my stories and songs.”

There was this big applause then, and afterward a rich-looking man with gray hair and a pinstripe suit came up to Grandma and they talked quietly for awhile. When they were done, Grandma came to me and Lea and Kayden and said goodbye. She said she was not going to wait for my parents to come home for a traditional funeral. She had a lot of living still to do since Buddha had given her the gift to live twice in one life, and this man, some famous novelist from Colombia, was going to take her places. He might even help her write a book. So she was going to the Mediterranean to get a tan and to Venice to see the festivals and ride the gondolas and maybe afterward she’d go by Hanoi and see what they’d done to her childhood home and visit some long-forgotten ancestral graves and relatives and then who knows where she’ll go after that. She’ll send postcards, though, and “Don’t you wait up.”

Then before we knew it, Grandma was already out the door with the famous novelist, and the elevator music started playing, and I swear, if those ice sculptures of swans started to fly away or something, nobody would have been surprised. Kayden and I ran out after Grandma when we got through the hugging frenzy, but she was already gone, and outside there was only this beautiful city under a velvety night sky, its high-rises shining like glass cages with little diamonds and gold coins kept locked inside of them.

Mama and Papa came home two days later. They brought incense sticks and ox-hide drums and wooden fish and copper gongs and jasmine wreaths and oolong tea and paper offerings—all the things that we were supposed to have for a traditional funeral. A monk had even sent a fax of his chanting rate and schedule so we could choose the appropriate time because he was real busy, and the relatives started pouring in.

It was hard to explain then what had happened, what we had always expected as the tragic ending of things, human frailty the point of mourning and grief. And wasn’t epic loss what made us tell our stories? It was difficult for me to mourn now, though. Difficult ‘cuz while the incense smoke drifted all over the house and the crying and wailing droned like cicadas humming on the tamarind tree in the summer back in Vietnam, Grandma wasn’t around. Grandma had done away with the normal plot for tragedy, and life after her was not going to be so simple anymore.

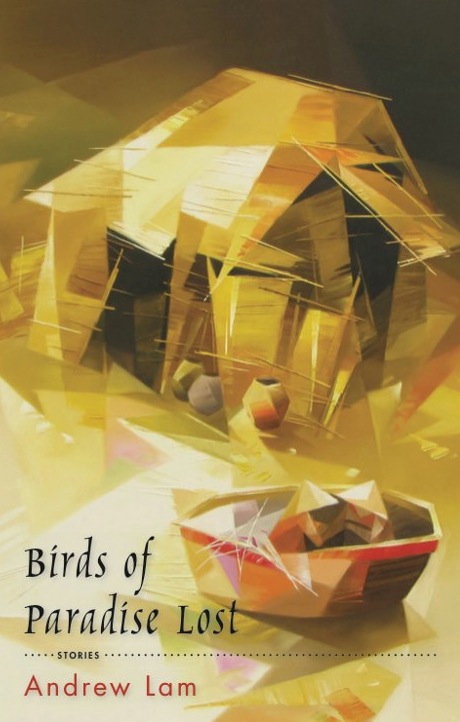

Art Information

- "Whimsy" © Daniel Hoherd; Creative Commons license.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, and East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres. He’s an editor and cofounder of New America Media, an association of over two thousand ethnic media outlets. He’s been a regular NPR commentator, and his essays have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Mother Jones, and many other journals.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, and East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres. He’s an editor and cofounder of New America Media, an association of over two thousand ethnic media outlets. He’s been a regular NPR commentator, and his essays have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Mother Jones, and many other journals.

“Grandma’s Tales” is reprinted from Birds of Paradise Lost (Red Hen Press, 2013), his first collection of short stories and a finalist for the 83rd California Book Award.

“Grandma’s Tales” is reprinted from Birds of Paradise Lost (Red Hen Press, 2013), his first collection of short stories and a finalist for the 83rd California Book Award.

This story has also appeared previously in print in Amerasia Journal (1994) and the anthology Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry and Prose edited by Barbara Tran, Monique Truong, and Khoi Truong Luu (Asian American Writers Workshop, 1998). You can listen to Andrew Lam read “Grandma’s Tales” on The Story, American Public Media (September 13, 2013).