"My Favorite Critic" by Lorraine Berry

The Best Criticism Conveys What It Means to Be Human

AWP 2014: Lorraine Berry will be moderating TW's upcoming panel "Literary Politics: White Guys and Everyone Else," where she and other writers will debate why it's so hard to break into the mainstream.

When Zadie Smith emerged on the scene with her 1997 novel White Teeth, I had mixed feelings. I was thrilled that the literary world was paying attention to a young woman of color. Yet, I’m suspicious when any wunderkind, barely out of her teens, is hailed as the savior of literature.

Still, my first impressions were wrong. Smith is everything her early novel showed her to be—acutely observant, satirical but also serious. Even more surprising, she’s become my favorite critic. No one else in today’s elite literary circles sounds quite like her. Here she is, in Vibe magazine of all places, on “The Zen of Eminem”:

Still, my first impressions were wrong. Smith is everything her early novel showed her to be—acutely observant, satirical but also serious. Even more surprising, she’s become my favorite critic. No one else in today’s elite literary circles sounds quite like her. Here she is, in Vibe magazine of all places, on “The Zen of Eminem”:

But let's settle on the bald facts: Eminem has secured his place in the rap pantheon. Tupac, Biggie, and Pun are gone, and right now there just isn't anyone else but Eminem who can rhyme 14 syllables a line, enrage the U.S. Senate, play the dozens, spin a tale, write a speech, push his voice into every register, toy with rhythm, subvert a whole goddamn genre, get metaphorical, allegorical, political, comical, and deeply, deeply personal—all in one groove of vinyl.

A search for critical articles written by Zadie Smith will take you from rap music to Katharine Hepburn to the heady writing of Karl Ove Knausgaard and Jaron Lanier. She’s a prolific critic, often found in the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker. She covers high and low culture, with all the baggage those categories carry. In fact, she writes the kind of criticism that gets to the undergraduates I teach. My students, pushed by me, are just learning how to read literary criticism. Smith makes it approachable, without dumbing it down.

Take "Generation Why?," a 2010 piece in the New York Review of Books. As in other essays, she focuses on digital life, a topic that's fertile territory for classroom debate. Smith addresses some basic questions: What does it mean to be human? And in the new world of social media, has our sense of humanity expanded or contracted?

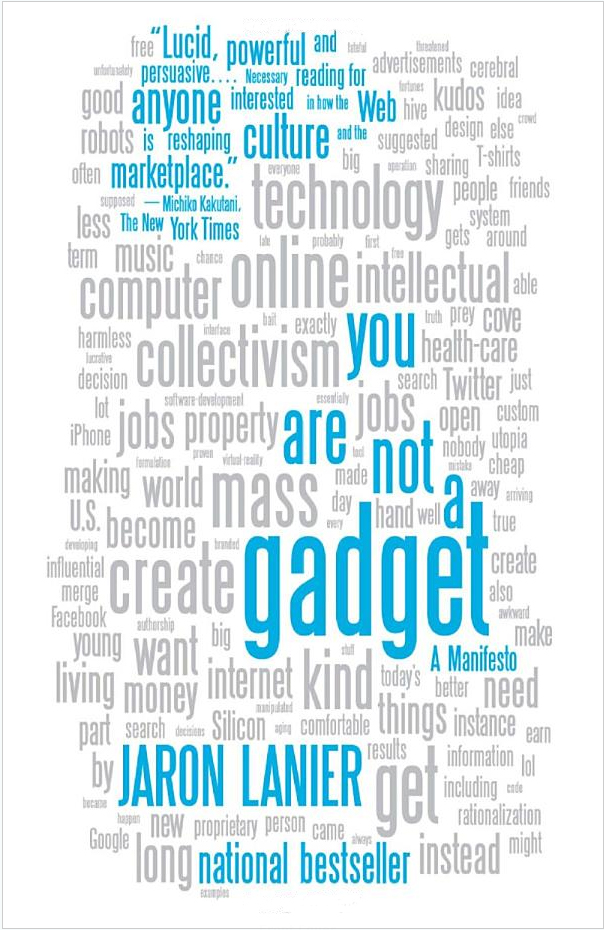

"Generation Why?" reviews the 2010 Aaron Sorkin film The Social Network about Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Smith contrasts that film with computer scientist Jaron Lanier's book of the same year, You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto.

Sorkin is from Generation 1.0. Smith notes that his film, far from a documentary, is an older man's attempt to understand a new way of life. Facebook's Zuckerberg is from Generation 2.0, the cohort who grew up using computers. But even though only nine years separate her from Zuckerberg—Smith was born in 1975 in London—she claims they're from different generations. While a fellow at Harvard's Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, she overlapped with Zuckerberg, but Smith “felt distant” from him, she writes, “and all the kids at Harvard.”

In You Are Not a Gadget, Lanier argues that we’re changing our understanding of what it means to be human in order to fit within the narrow confines of social media platforms. “What Lanier, a software expert, reveals to me, a software idiot,” Smith says, is that “software is not neutral.” She then adds, magnificently:

When a human being becomes a set of data on a website like Facebook, he or she is reduced. Everything shrinks. Individual character. Friendships. Language. Sensibility. In a way it's a transcendent experience: we lose our bodies, our messy feelings, our desires, our fears. It reminds me that those of us who turn in disgust from what we consider our overinflated liberal-bourgeois sense of self should be careful what we wish for: our denuded network selves don't look more free, they just look more owned.

Exactly. Smith’s understanding that the desire for transcendence is both human and a potential trap, rings true for me. In particular, Facebook became a problematic way of sharing my life when my father took sick and died last spring. I didn't post often during that period, but I did update what was going on every few days, and scores of my Facebook friends left messages of concern on my page. At the same time, it felt so impersonal. Many of the messages were from people I had never met in person. They didn't know my father. It was not the same as a letter written by a friend.

I'm not sure why I expected more from Facebook—I see this as my fault, my vain hope that my father's death could be made less painful through the ease of virtual connection—but I discovered it was not a place where I could properly mourn.

When my students read “Generation Why?” for one of my classes in 2012, they took umbrage at Smith’s idea that they could be reduced to their Facebook identities, even as they admitted that a portion of their quotidian lives is spent on Facebook. Then, just twelve months later, when I once again discussed Facebook in class, that group of students told me they were using it less frequently.

When my students read “Generation Why?” for one of my classes in 2012, they took umbrage at Smith’s idea that they could be reduced to their Facebook identities, even as they admitted that a portion of their quotidian lives is spent on Facebook. Then, just twelve months later, when I once again discussed Facebook in class, that group of students told me they were using it less frequently.

Why? Because it’s not "theirs" anymore. Too many older folks are on Facebook now, they say. And yet, Smith’s and Lanier’s trenchant criticism gets under their skin more than ever.

With Twitter, Snapchat, and newer forms of social media, young people may be compressing even more of their personalities. Recently, I found myself privy to a conversation between two students in which they discussed how "long" they could wait before responding to a text: If you do it immediately, you seem needy; if you wait more than ten minutes, you seem rude. Students adhere to such rules of engagement, yet continue to argue with me that they’re not slaves to their gadgets.

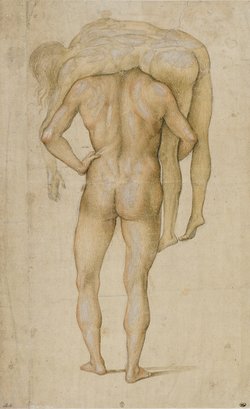

In her 2013 NYRB essay “Man vs. Corpse,” Smith draws parallels between the work of literary writers like Knausgaard and Tao Lin with Italian master painters who confronted the wholeness of the human being—including the reality of death:

Elsewhere, death is rarely seriously imagined or even discussed—unless some young man in Silicon Valley is working on permanently eradicating it. Yet a world in which no one, from policymakers to adolescents, can imagine themselves as abject corpses—a world consisting only of thrusting, vigorous men walking boldly out of frame—will surely prove a demented and difficult place in which to live. A world of illusion.

On Facebook, it’s not uncommon for others to continue to post on the deceased's page, as if she or he were still present and able to interact. After a recent controversy over whether the dead would be allowed to have their own “look-back” movies on Facebook, Mary Elizabeth Williams of Salon quotes one Facebook representative as telling the BBC: “This experience reinforced to us that there’s more Facebook can do to help people celebrate and commemorate the lives of people they have lost."

But like Smith, I believe the Internet distances us from death. I wish I could get my students to understand what she's talking about when she writes:

Walking corpses—zombies—follow us everywhere, through novels, television, cinema. Back in the real world, ordinary citizens turn survivalist, ready to scale a mountain of corpses if it means enduring. Either way, death is what happens to everyone else. By contrast, the future in which I am dead is not a future at all. It has no reality. If it did—if I truly believed that being a corpse was not only a possible future but my only guaranteed future—I’d do all kinds of things differently. I’d get rid of my iPhone, for starters. Lead a different sort of life.

Perhaps then my students would find a way to get off their phones and relearn the art of face-to-face conversation, of knowing each other as something more than electrons. I still hope a few of them, young as they are, have caught a glimmer of the reality of death conveyed by Smith and the writers and artists she admires: Death comes for us all, and spending your life tied to machines is no way to live.

The answer for Smith, as she revealed last December in “Man vs. Corpse,” was to give up her Facebook account. While I have not done the same, I post on Facebook far less frequently and rarely use Twitter. Right now, I long for the direct contact of touch and hugs—of handwriting on a page—to make me feel more human. And Zadie Smith reminds me of my humanity, including the fact that sadness is as much a part of life as the easy "likes" and "shares" of virtual existence.

Publishing Information

- “The Zen of Eminem” by Zadie Smith, Vibe, January 2005.

- "Generation Why?" by Zadie Smith, New York Review of Books, November 25, 2010.

- You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto by Jaron Lanier (Knopf, 2010).

- "You Are Not a Gadget: OS Book Review with Kent Pitman” by Lorraine Berry, Open Salon, February 25, 2010.

- "Man vs. Corpse" by Zadie Smith, New York Review of Books, December 5, 2013.

- "Death on Facebook Now Common as 'Dead Profiles' Create Vast Virtual Cemetery" by Jaweed Kaleem, Huffington Post, December 7, 2012.

- "Can Facebook Help Us Grieve?" by Mary Elizabeth Williams, Salon, February 7, 2014.

Art Information

- Photographs of Zadie Smith © David Shankbone; Creative Commons license.

- "Man Carrying Corpse on His Shoulders" by Luca Signorelli (circa 1500); public domain.

Lorraine Berry is a senior editor at Talking Writing.

Lorraine Berry is a senior editor at Talking Writing.

She teaches creative nonfiction and is the project director for NeoVox, an online magazine published at SUNY Cortland. Her work has appeared in Salon, Dame, Bitch, Diagram, The Raven Chronicles, and other magazines. Her memoir Word Lovers has been optioned, and she's currently at work on several projects that examine gender, race, and literature.

When not writing, she can be found exploring the woods with her two dogs, hanging out with her daughters, or taking on the world with her partner, Rob.