By Angela M. Graziano

I imagine every family has a set of stories they share. At holidays, birthdays, and reunions, they’re the stories told over and over, sometimes out of kindness, sometimes for humiliation purposes.

My family has a whole canon. There’s the one about my grandfather who, in an effort to disguise his baldness, polished his entire head black with shoeshine crème. The time my cousin, aggravated with her husband and his friends, made them a Superbowl-friendly serving of nachos made with dog food instead of ground meat. The toppling Christmas tree that left my grandmother’s Gucci-clad feet poking from beneath giant pine boughs (the only injuries came from the persistent laughter of bystanders).

They’re all classics, though none compare to my parents’ accidental break-in—my parents, the same people who still regularly recite the lyrics to “It’s a Small World” to lift someone’s spirits. But in 1995, the summer I turned sixteen, they proved that even June and Ward Cleaver can harbor a bit of Bonnie and Clyde.

It was a typical Sunday morning. My father busied himself with organizing frozen grapes and boxes of Ring Dings into a cooler, while my mother loaded her straw bag with women’s magazines. Then my sister and I broke the news: no beach day for us.

“Suit yourselves,” my father said. “But I’ve got big plans for today.”

His daughters had chosen an air-conditioning vent over him. He gathered several pink beach buckets, in case, I suppose, he and my mother decided to befriend a group of seven-year-olds.

“Big plans,” he said.

My sister and I stood at the front door as our parents backed out of the drive. “We still have room for two more,” my father shouted, beeping the car horn.

We waved politely before running back into the house, where we grabbed a gallon of ice cream and flipped on the TV.

I remember lying on the sofa, watching trashy infomercials, the air conditioning numbing the back of my neck. I tried to imagine how our parents would survive without us. Perhaps they’d do something romantic and middle-aged. Enjoy a beachside walk. Kick their feet in the surf. Feed one another bites of cotton candy. Take a Ferris wheel ride.

• • •

“For Christ’s sake, just act like you own the place,” my father says to my mother and clicks on the car blinker. “It’s a club. You know how many people must go in and out of the place every day? Just act like you belong, and you’ll be fine.”

“I don’t think it’s a good idea.” My mother taps the window frame. “What if they check us for special badges or something?”

My father turns the steering wheel and starts down the long, paved drive.

“Look,” he says. “No gate! If they wanted to keep nonmembers out, they would have a gate.”

He parks beneath a large, striped awning and cuts the engine. He briefly glances at the rearview mirror and adjusts the few blondish curls that creep from under his Walt Disney World baseball cap.

“You can’t just leave the car sitting here,” my mother says.

“I’m sure there’s a parking lot out back and some kid working valet.” My father tosses his key ring onto the driver’s seat. He pulls a dental pick from his pocket and wedges a short piece of floss between his teeth, as though he were in his dentist’s waiting room and not in the driveway of one of the most elite properties in the state. “He’s probably just parking someone else’s car.”

My father flicks the used pick into a nearby rosebush without a second thought. He casually whistles the Flintstones theme. His sandy bathing suit bottoms swoosh as he makes his way toward the giant wooden front door of the estate.

“Trust me,” he says, tousling my mother’s hair. “Everything will be fine.”

• • •

When I was a kid, my father already had his eye on the Club. It was part of what he called “Rich People Road”—a stretch of several miles that hugs the New Jersey coastline and consists of houses the sizes of small countries. Most of these domestic monstrosities are home to local celebrities and CEOs.

To my father, the fact that these people lived within driving distance of our small suburb seemed impressive. To me, the fact that the homeowners were wealthy enough to afford spiral slides for their backyard swimming pools made them inherently more important than us.

Driving down Rich People Road was a summertime ritual throughout my childhood. My father would happily whistle out a little tune and buzz down all the car windows. Within seconds, the sticky summer air would leave our skin dripping with salty sweat.

But for my dad, it was worth it to see what lay at the end of the street. There, situated among the multi-million-dollar estates, was something so rare, so redolent of success, that it was worth driving past several times every season: what he long referred to as the “New Jersey Croquet Club.”

“Just look at that place,” he’d say, slowing the car to a crawl. Despite the snaking line of traffic behind us or my mother’s foot slamming against the make-believe gas pedal on the passenger-side floor, my father would creep past what he believed was our state’s finest croquet club in a sluggish, stalker-like fashion.

There was no sign announcing the structure as a club. Not a single New Jersey tour book included a passage on the illustrious place. None of my father’s friends or colleagues had ever heard of it. However, he knew it was a croquet club.

In his defense, all the details pointed to a club. The main house was so large it made the other homes on the block look like cabañas. Its sprawling lawns sparkled with dew, as though an art director had precisely placed each drop. The structure itself, modeled after a British country-style estate, had so many wings it could easily have been mistaken for an upscale shopping mall. And for years, no matter when our family drove past the “Croquet Club”—June, July, August, and sometimes even early September—there was always a game of croquet taking place on one of the vast lawns.

“Woo woo,” my father would whistle and remove his hands from the steering wheel in a momentary fit of glee. “Look-at-that-place! A real beauty. Now, if everyone pays attention, we might get to see some movement on the field.”

• • •

In terms of efficient navigation, my family and I never had a real reason to travel down Rich People Road. We were not members of any elite social class. We were never invited to high tea on one of the estates. We weren’t buddies with any of the homeowners or, for that matter, any of the groundskeepers.

Still, my father came up with crafty reasons for why we had to take the scenic route on the way to the beach our family frequented:

“Highway traffic is going to be backed up for miles on a day like this,” he’d explain before making an illegal U-turn toward the high-society strip.

“Heard about an old-fashioned ice cream shop just down the road from that street with all the big houses. You know which street I mean,” he’d say casually, as though the road weren’t embedded in our family’s collective memory.

“Well, maybe if you kids hadn’t taken so damn long to get ready this morning, we wouldn’t need a shortcut” was another popular excuse.

But in retrospect, I think my father had deeper intentions for those drives. Rather than giving his daughters high fives when they aced a spelling quiz or kicked the winning goal, he would cruise us past billion-dollar estates so we could ogle the good life.

He grew up in the same blue-collar town where his parents had been raised and where he was raising his own children. Yet unlike our neighbors, men and women who never dreamed of having access to such wealth—let alone the audacity to try to catch a glimpse of it—my father was different. He had always wanted more. A hardworking man proud of every cent he earned, he never accepted the idea that social classes actually exist.

He worked just as hard at his local design business as any Wall Street professional, he’d say. All the trips we took down Rich People Road were his version of motivational speeches—his way of showing us there’s still something to be said for having dreams.

“Bet you not all these people came from wealthy families,” he’d point out as we drove past wrought-iron security gates. “Bet you some of them had to make something of themselves. And if you keep working as hard as you have been in school”—he’d eye my sister and me in the rearview—“you might be neighbors with these folks someday.”

Then shortly after we viewed what appeared to be a series of small New England universities, we’d arrive at our ultimate destination: a splintering boardwalk with neon lights, half-dilapidated amusement rides, and $1.50 Steak-Um sandwiches.

If motivating us was what my father sought, he achieved it. My sister and I would gaze at the antique roadsters parked in every drive, the prize-winning rose gardens just glimpsed through two-story hedges, the ivy on the ancient stone walls. From the cloth backseat of our 90-degree Mercury sedan, we’d pledge to write multiple book reports about War and Peace if it meant a chance to call one of those estates home.

• • •

Talk of the Croquet Club far exceeded the summer season in our family. It became a regular fixture of conversations throughout the year. “Bet they’re getting the lawns ready down at the Club,” my dad might mention in early spring. “Ahh. Another great day for a game of croquet,” he’d say in late fall, as if he, too, often enjoyed the luxury of the game.

But as the years passed, my sister and I began to roll our eyes. For us, the allure of the Croquet Club became tarnished. No longer did I toss my teddy bear into a somersault at the thought of the rich and famous. Instead, while traveling down Rich People Road, I’d ask my father to turn up the AC before I turned up the volume of my Walkman.

On the afternoon of the accidental break-in, our lack of enthusiasm didn’t discourage him. In my mother’s version of the story, the fact that no one else had ever heard of the Club also didn’t cross his mind. How could he have thought of such a thing, she asked, once he became consumed with the lavish interior of the place?

The inside of the Club resembled a museum, she told us later. But not the fun, interactive sort of museum our family visited; it was like the type with red velvet ropes and signs reminding visitors not to touch anything, including themselves. A suit of armor in a corner would not have looked unusual. It was the type of place where equestrian paintings went to die.

Now I often envision the initial moments of my parents’ break-in. I like thinking about them surrounded by the foreign, rich décor—my mother in her flowered bathing suit, cotton cover-up, and plastic sandals; my father with his K-Mart headphones dangling around his neck, buzzing with sports radio.

In my mind, they casually run their fingers across the various antiques, deep mahogany built-ins, and silk wallpaper. It doesn’t occur to them that the Croquet Club has no sign-in desk. They don’t notice the lack of other members mingling in the entranceway. I can just hear my father saying the members must be with the valet boy, chatting out back.

It doesn’t matter. Because as my parents make their way out of the foyer and into the grand room, they see the view they’d only imagined from their passing car for years. There, just behind a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows, is the Atlantic Ocean—and just before it, acres of perfect green lawn.

• • •

“Look at this place,” my father says, his eyes on the ocean. “People must pay a killing for memberships here. Do you see any sort of literature lying around?”

But before he and my mother start to search for pamphlets, they glimpse what makes the whole trip worthwhile: a game of croquet starting up just outside the glass.

As my father steps into the backyard, he thinks about joining the game. Then the other Club members will welcome him and my mother to an impromptu lunch.

“Pardon me. But who in the hell are you?” asks a middle-aged man in a crisp sport coat.

“Oh, hello, there,” my father says, helping himself to a cracker-full of steak tartar from the man’s table. “We’re just taking a look around. I must say, it’s a pretty nice place.” He spits crumbs from the sides of his mouth.

The man looks at a few other men and women seated at a nearby table. Two of the men stand and walk toward my father, but the man in the sport coat stops them.

“Yes,” he says. “I like to think it’s a pretty nice place.”

“So.” My father pats him on his well-tailored back. “What’s the membership at a place like this go for? You have any literature around that we can take with us?”

“Literature?” the man asks.

“Yeah, you know, like a brochure,” my father says.

My mother begins to backwards-walk her way into the house, cautious of potential guard dogs. Her hands firmly planted at her sides, she’s suddenly careful not to touch anything and risk leaving behind fingerprints.

“Sir,” the man says to my father. “What do you think this place is exactly?”

My father looks at the man, confused. He reaches toward an olive platter.

“What do you mean? It’s the Croquet Club.” My father nods at the game taking place on the lawn. He glances back at my mother, rolling his eyes at the man’s obvious naïveté.

“Club? Sir, this is a private residence,” the man says. “This is no club. This is my home.”

• • •

According to my mother, she and my father didn’t speak much on their car ride back. But my mother did speak as soon as she walked through the front door of our house.

“Hey, how was the beach?” my sister and I chorused, quickly trying to hide the remnants of our junk-food binge beneath a set of throw pillows.

“We didn’t make it to the beach,” my mother announced coolly. “We broke into a billionaire’s home instead.”

The story grew in the telling, of course, as family stories do. But my father never drove us past the Croquet Club again. The illusion of it was gone.

His hope of motivating his daughters lived on, however. He no longer encouraged us to do well on our math exams so we could eventually purchase memberships to the classiest club in our state. But he did remind my sister and me that really nice people can find a way to make something of themselves.

Like those friendly billionaires: Instead of calling the cops or taking “unnecessary measures,” they had listened to my dad’s side of the story, shared with him a short-lived laugh—then politely asked him to get the hell out of their house and never return.

Art Information

- "Blairsden, a large mansion owned by C.L. Blair: view of front of house" © Wurst Bros., 1903; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- "Croquet" © J. Ronald Lee; used by permission

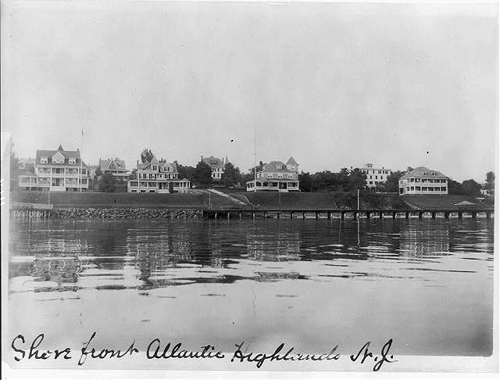

- "Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: shore front and Victorian houses" © Roberts and White, 1905; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

Angela M. Graziano’s work has appeared in print and online in the Apple Valley Review, Ariel, Design Sponge, Dislocate, Lost, and Portal Del Sol, among other publications. Her essays have appeared in several anthologies including Tarnished (Pinchback Press, forthcoming).

Angela M. Graziano’s work has appeared in print and online in the Apple Valley Review, Ariel, Design Sponge, Dislocate, Lost, and Portal Del Sol, among other publications. Her essays have appeared in several anthologies including Tarnished (Pinchback Press, forthcoming).

Angela is the founding editor of Something Green Events, an eco party-planning blog. Her first memoir, A Vision of Neon, is forthcoming from Serving House Books.