By David Biddle and Martha Nichols

Why Higher Prices Are Good for Authors

E-book “price-fixing” has a scurrilous ring, as if a bunch of shadowy hoods in business suits have been deciding the fates of humble readers. But in April 2012, that’s exactly what the U.S. Department of Justice accused five of the six big publishers and Apple of doing with e-book prices.

E-book “price-fixing” has a scurrilous ring, as if a bunch of shadowy hoods in business suits have been deciding the fates of humble readers. But in April 2012, that’s exactly what the U.S. Department of Justice accused five of the six big publishers and Apple of doing with e-book prices.

To date, all the publishers—Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins, Penguin, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster—have settled with the DOJ. (The “Big Six” of corporate publishing are now down to five; Random House is merging with Penguin.)

But when the publishers started settling last year, some with undue haste, an important opportunity was lost. We need a public discussion of the economics of creating and producing books. Settlements without a trial, in which nobody admits wrongdoing, have a way of obscuring unresolved issues in the midst of major business transformations.

The biggest question mark concerns authors and how we’re supposed to earn a living by writing books. We’re the workhorses behind the whole moneymaking chain, but we are still, usually, the last to profit.

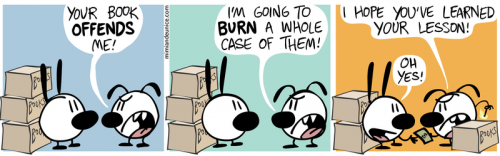

The current bench trial against Apple, the lone holdout, gives us a peek behind the curtain of corporate book commerce. More than that, we should be grateful to Apple for hanging tough on its business approach and facing down the DOJ in a New York City courtroom. We literary types need to push for terms that favor the creative work of writers—not price-chopping strategies that turn e-books into the equivalent of toilet paper rolls.

Thus far, the e-book pricing debate has been controlled by battling corporations, with little input from readers and authors. In fact, a September 2012 summary of the court decision at the Authors Guild website points out that in their original charges, “the DOJ didn’t bother submitting a single economic study about the likely effects of the settlement on the market. An incredible result.”

That’s probably because any economic study you read will be based on data that’s several years old. The e-book business is in flux, and from where we sit, the shelf life of research in the e-book world is near zero.

In the absence of solid information, it’s easy for power players to set the terms behind closed doors, and that’s usually the worthy motivation for price-fixing lawsuits. But in this case, the U.S. government is on the wrong side of what’s good for writers.

So, let’s talk about the DOJ’s antitrust argument, the issues publishers were trying to address in their so-called price-fixing scheme, and the new opportunities writers have to make far more than they did under traditional royalty schemes.

Amazon’s Monopoly: The Wholesale Model

Before Apple stepped onto the scene in late 2009, Amazon controlled the e-book game. Some estimate that Amazon had a 90 percent market share at the time. Nobody else was selling e-books, except on the self-publishing fringes.

The wholesale model Amazon forced on publishers was similar to existing print distribution arrangements. Publishers sold Amazon the rights to e-books at a discounted price—usually 50 percent of the hardcover list price. Amazon and other digital book retailers like Barnes & Noble could then offer the e-book at whatever price they wanted. Back then, Amazon’s top price for e-book versions of bestsellers was typically $9.99.

Most industry analysts believed $9.99 was too low for the health of the publishing industry. Among other things, it threatened the first-run hardback book market, in which print copies were priced between $25 and $35.

As Carolyn Reidy, CEO of Simon & Schuster, said last week during her testimony in the Apple case, Kindle pricing was “devaluing” her product.

Some critics claim that Amazon’s $9.99 price for a bestselling e-book was too low to generate an acceptable profit margin even by Amazon’s standards. It’s quite possible that Amazon was taking a loss-leader approach to book sales in order to sell more Kindles.

No one has yet verified whether that was or is Amazon’s plan. But a public hearing can reveal such hidden strategies. To whit: On Day 3 of the Apple trial, Russell Grandinetti, VP of Kindle content at Amazon, took the stand.

As reported in Fortune, Grandinetti theorized that the publishers had a “monopoly” on their books and were bullying Amazon. “It was our belief that the reason we were in this situation was that some of the publishers wanted to slow the sale of the Kindle,” he said.

Note whom he tagged as a “monopoly” and how cleverly he made the Kindle’s success the publishers’ problem.

Publishers Fight Back: The Agency Model

Publishers Fight Back: The Agency Model

When Apple’s iBooks Store and the iPad were unveiled in early 2010, they were a serious threat to the Kindle market. By that point, publishers were also itching for more direct control over pricing—and Apple was happy to oblige.

The book publishers pushed for a model similar to the one Apple had set up with its iTunes Store, in which Apple, as retailer and distributor, takes a cut of each song purchased. The publishers dubbed this the agency model for e-books.

Apple’s initial agency model agreement gave the iBooks Store (and other retailers like Amazon and Barnes & Noble) a 30 percent commission on each e-book sold; the publisher got the remaining 70 percent. Apple negotiators also demanded “most favored nation” status—a guarantee that the big publishers involved would give Apple the best deal on their products.

The tricky part? Getting Amazon to agree. The agency model meant publishers and Apple set prices for e-books, not Amazon or any other retailer. Apple, it appears, did the legwork in communicating and organizing this new approach to the five publishers. Because all the major players agreed to hold firm on the terms of the agency model in order to force Amazon’s hand, it looks like collusion.

For the DOJ, this is price-fixing—a big antitrust no-no. A cartel of publishers influenced by Apple tried to strong-arm Amazon and B&N into setting higher prices. Retailers in a free market system are supposed to have the right to price products as they see fit.

The problem with this antitrust argument is that retailers like Amazon have been doing their own strong-arming for years. Sure, by controlling prices, the big publishers were looking to stick a thumb in Amazon’s eye. But Amazon is the Wal-Mart of the Internet. Its business model is all about driving prices down in order to crush the competition.

Everyone’s a Villain

Without a doubt, the publishers thought that industry control of prices for e-books was fair. Book publishers need to make a predictable profit in order to keep their marketing and development machines well oiled.

Early in 2012, Macmillan U.S. CEO John Sargent argued on the company’s website that Macmillan’s “disagreement [with Amazon] is not about short-term profitability but rather about the long-term viability and stability of the digital book market.”

Meanwhile, Apple executives still insist they did nothing wrong in promoting a model similar to its agreement with the music industry.

Orin Snyder, the lead lawyer representing Apple, said in his opening statement last week that innovations such as Apple’s iTunes and App Store have poured billions of dollars into the U.S. economy. For promoting the same innovative approach to selling e-books, he added, “Apple should be applauded, not condemned.”

We do applaud Apple for going to court, although not because it’s the spunky hero of this saga. Rather, Apple’s trial has now become a public forum in which a good deal of the emperor’s clothes are being stripped away.

Just last week, Google’s Thomas Turvey, director of strategic partnerships, took the stand. In a previous written statement, he’d claimed that in early 2010, all the publishers involved told him Apple had persuaded them to move to the agency model. But under cross-examination by Apple’s Orin Snyder, Turvey couldn’t remember the name of a single publishing executive, date of conversation, or location of discussion.

Turvey eventually admitted that his lawyer had helped him prepare his statement and that it was “likely” that publishers had talked to people on his team. Turvey also said under oath that Apple was one of Google’s main rivals.

“The confrontation played out like a scene from Law and Order,” Greg Sandoval reported in the Verge. Snyder “shredded” Turvey’s testimony—so much so that Judge Denise Cote “mercifully” adjourned with “Let’s allow Mr. Turvey to escape so he can enjoy his Thursday.”

Had Apple’s leaders decided not to press its agenda, we would all have been poorly served by our justice system. Apple isn’t exactly a white hat, but neither is Google or Amazon—and Amazon still has about 65 percent of the e-book market.

Unexpected Winners: Writers

Control of electronic reading technology is far more important in the long run than the pricing system used to sell books. It’s been more than three years since the battle between the Kindle and the iPad began. The latest figures show that multimedia tablets like the iPad are winning big (and that’s not taking into account all the e-reader apps for smartphones).

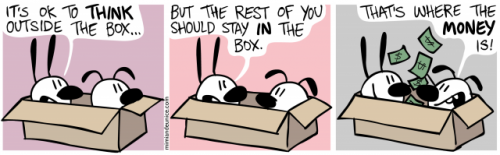

Yet, the technology issue is just one aspect of the new publishing frontier. Traditional publishers offer, at most, 25 percent royalties to authors on the net price of books they sell. Amazon and other online distributors currently offer 70 to 80 percent for e-books sold. That means authors have a lot to gain by publishing their own books and taking their cut directly—and Amazon makes it easy to do so.

Established authors like Joe Konrath and Barry Eisler are making a killing selling their work in the indie marketplace. Even mega-bestselling authors like Stephen King understand why self-publishing can bring a big payoff. In 2000, when he began self-publishing and selling some of his own work, King’s website trumpeted: “My friends, we have a chance to become Big Publishing’s worst nightmare.”

Ironically, Amazon’s arrangement with indie authors through its KDP Select system is now a version of the agency model. As long as an indie is willing to price his or her work between $2.99 and $9.99, the author receives 70 percent of the sales. Yes, there are price limitations, but the author determines that price, not Amazon.

The real point here is that Amazon can’t just cut an indie book price for its own strategic purposes, which is what its wholesale model originally required of corporate publishers.

These days, every writer and reader needs to pay careful attention to the profit-making shenanigans of the publishing world. Our dependence on digital distributors like Amazon, B&N, and Apple makes us even more vulnerable to all sorts of corporate whimsy.

But one of the most surprising outcomes of the Apple case may be that writers have much to gain in the new media world. That’s why it’s essential that authors understand the choice they now have between going indie or submitting work to a traditional publisher. This is a financial choice, not just a matter of personal taste. In fact, the agency model could be a boon to writers, especially for those who get a greater percentage of book sales up front than they ever did with standard royalty contracts.

Correction, June 14, 2013: References to the "Big Six" publishers have been changed to five in order to avoid confusion over which book publishers ended up sued by the DOJ and subsequently settled.

More About the DOJ, Apple, and E-Book Pricing

While the trial continues in New York City, set up Google Alert and other RSS feeds to notify you whenever there’s more news coverage of Apple and the DOJ. Follow relevant tweets from digital publishing-business watchers like The Passive Voice and GalleyCat. Get it all when it’s hot off the press…er…screen.

For more about pricing e-books from an indie author’s point of view, see “How Much Should E-Books Cost?” by David Biddle in Talking Writing, Winter 2013.

For links to the information and quotes cited in this article, see the list below. This list also provides background on the DOJ’s original case against the publishers and even a piece about why the suit against Apple may end up in the Supreme Court.

-

"Court Approves Justice Department’s E-Book Proposal, Restoring pre-2010 Status Quo Without an Economic Study," Authors Guild, September 7, 2012.

-

"S&S’s Reidy Is Next at the Apple Trial" by Calvin Reid, Publisher's Weekly, June 6, 2013.

-

"Day 3 of the Apple E-Book Trial: Enter Amazon" by Philip Elmer-DeWitt, Fortune, June 6, 2013.

-

"A Message from Macmillan CEO John Sargent," News: Macmillan Site.

-

"U.S.A. v. Apple Day 1: Calling Eddy Cue" by Philip Elmer-DeWitt, Fortune, June 3, 2013.

-

"Google Helps DOJ Make First Big Mistake in Apple E-Book Trial" by Greg Sandoval, The Verge, June 6, 2013.

-

"Meet Orin Snyder, the Deadliest Trial Lawyer in Tech" by Greg Sandoval, The Verge, June 10, 2013.

-

"Stephen King's New Work Only on Internet," ABC News, July 20, 2000.

-

"It's an Apple and Amazon World..." by Jack W. Perry, Digital Book World, June 7, 2013.

-

"The Case Against Apple" by Andrew Albanese, Publisher's Weekly, May 25, 2013.

-

"E-Books: Defending the Agency Model" by Frédéric Filloux, Guardian, March 12, 2012.

-

"The Tablet Is Killing the E-Book Reader: Study Says Shipments to Fall 36% This Year" by Todd Bishop, GeekWire, December 12, 2012.

-

"Customer FAQ for Attorneys General E-Book Settlements," Amazon website.

-

"This Is Why DOJ Accused Apple of Fixing E-Book Prices" by Greg Sandoval, CNET, April 11, 2012.

-

"Publishing Is Broken, We're Drowning In Indie Books—And That's A Good Thing" by David Vinjamuri, Forbes, August 15, 2012.

-

"Apple iBooks at 24% Worldwide E-Book Market Share? One Analysts Thinks So," Digital Book World, February 28, 2013.

-

"U.S. v. Apple Could Go to the Supreme Court" by Roger Parloff, Fortune, June 5, 2013.

David Biddle is a contributing writer at TW. His Talking Indie column recounts the ups and downs of being an independent publisher. You'll find information about his novel Beyond the Will of God and other digital fiction on davidbiddle.net.

David Biddle is a contributing writer at TW. His Talking Indie column recounts the ups and downs of being an independent publisher. You'll find information about his novel Beyond the Will of God and other digital fiction on davidbiddle.net.

"I felt sleazy and pathetic. I’d been reduced to begging my family and friends to buy my book."

— "Sorry, Your Buddies Won't Buy Your Book"

"Emily Dickinson is our 'Zombie Mother,' as Legault invokes her: an undead goth girl. Or my middle-aged contemporary, facing mortality yet lifted by a sardonic desire to dish with God." — "Emily Dickinson, Zombie"