Theme Essay by Andrew Vanden Bossche

Every Batman Is the Batman We Need

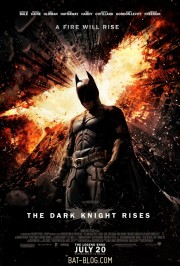

This summer, Batman saved everyone again. Director Christopher Nolan's Batman isn't my favorite, and his blockbuster movie The Dark Knight Rises isn't my favorite of Nolan's Batmans, but he knows how to deliver the Caped Crusader we need—maybe the one we deserve, too.

In a world that includes the Occupy movement and Islamic terrorists, it’s clear that mainstream movie audiences want a Batman who will do whatever it takes to protect America. Played by Christian Bale, the Dark Knight, according to the film's website, returns to Gotham City to take on a new threat: “a masked terrorist whose ruthless plans” involve rallying an anarchic mob to battle the Gotham cops.

In a world that includes the Occupy movement and Islamic terrorists, it’s clear that mainstream movie audiences want a Batman who will do whatever it takes to protect America. Played by Christian Bale, the Dark Knight, according to the film's website, returns to Gotham City to take on a new threat: “a masked terrorist whose ruthless plans” involve rallying an anarchic mob to battle the Gotham cops.

At one point, Batman stands atop a police cruiser, surveying the scene like Patton on a tank.

All Batmans have satisfied the zeitgeist in this way. Superman saves the world from physical threats, but it's Batman who saves America from its existential fears—be they gangsters, the corrupt and wealthy elite, or leftist protestors.

Yet, what I love most about Batman is not just Batman—the man or the original DC Comics character—but the way Batman can be turned into almost anything. For the same reason, I love Shakespeare, not just for his beautiful language, but for the infinite universe of Hamlets and Romeos and Juliettes and King Lears, all those interpretations over the centuries in ever-changing substance and glittering variation.

Comic book nerds like me have a reputation for complaining to a ludicrous degree about adherence to source material—Should Wonder Woman wear pants or a skirt? How much blue should be on Spider Man's costume?—but most of us actually appreciate a new author’s take on an old hero. Batman, perhaps because of the sheer variety of roles he's played, has no definitive Batman story for purists to cling to.

And for me, every story about Batman is better than the original, each a unique spin on a man in a costume who fights crime.

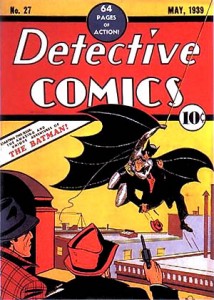

The original Batman first appeared in a 1939 DC issue of Detective Comics. Although he soon became popular enough to merit his own series, his roots have stayed true. This World War II-era Batman came with the backstory still associated with him: As a child, wealthy Bruce Wayne saw his parents brutally murdered and vowed to take revenge on all criminals. “The Bat-Man” was his secret identity, known only to his loyal butler Alfred and his sidekick Robin, “The Boy Wonder.” He was a gritty noir hero who shot guns and had no compunction killing crooks. Even if he fought crazy villains, the original Batman was grounded firmly in fighting the reality of the organized crime and corruption of the day.

He was quite serious, just as Nolan’s contemporary adaptation of the Dark Knight is. But contrast these noir and neo-noir versions with the TV Batman of the 1960s. One of the funny things about superheroes is that they’re all ridiculous, really, and Adam West’s Batman embraced the absurdity. Watching it now, long after the dayglow '60s, I find his Caped Crusader charming. Rather than a superhero, Batman was a bored billionaire who dressed up in costume to fight other rich eccentrics like the Penguin, Riddler, and Joker.

A deliberate camp parody, the Batman TV show sashayed in to pick up the pieces of a comic series that, at the time, had been driven to imaginative ruin by an increasingly bizarre parade of space aliens and sci-fi gizmos.

In the early 1990s, though, Adam West’s campy Batman meant nothing to me. The economy had collapsed—again. At seven, I’d already learned that bullies were real and that life wasn't fair and that bad things happened to good people. I also suspected that bad guys weren't bad just because they loved being evil.

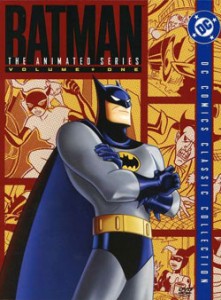

The Batman I most needed then was Batman: The Animated Series, which first aired on Fox in 1992 and was primarily the work of stylish animator Bruce Timm. Meant for kids, The Animated Series nonetheless presented a much darker Batman than any since the DC original. The result was a show that, unlike almost all cartoons aimed at children and most aimed at adults, didn't treat its viewers like idiots.

In The Animated Series, Batman's world is shadowy and spooky, an unfriendly place where tragic things happen. Batman always gets the villain in the end, but he doesn’t always make everything right. What’s more, the villains aren't always bad people, and none of them start out evil. The creators of this series didn't rip its stories from the front page; instead, they focused on making the characters feel human.

Consider Mr. Freeze, who used to be little more than a mad scientist with a penchant for puns based on his gimmicky name. (The ‘60s TV show had him kidnapping an Icelandic supermodel and hiding her in a refrigerator.) In The Animated Series, he’s a tortured, wrathful man willing to do whatever it takes to save his wife from a terminal illness. One episode with Mr. Freeze, “Heart of Ice,” won a 1993 Emmy for outstanding writing.

Catwoman, meanwhile, spends her stolen money fighting for animal rights, and Clayface, a grotesque, shape-shifting monster, is the victim of a corrupt businessman's experimental drug. In this series, the nastiest villains don’t wear costumes, and they don’t go to jail. They’re mob bosses and the ruthless one percent who are above the law and know it.

In most cartoons, evil exists only in costumed villains, and fighting evil consists of throwing punches, a candy-bright gloss that blinds children to what true injustice looks like. In Batman: The Animated Series, fighting injustice seems much, much harder.

And the best thing? This Batman could be weak or strong. The writers changed around the storylines, including episodes where kids learn to be grownups by protecting their hero, or in which Batman grieves the death of his parents. In another episode, he reunites two brothers, one a mob boss, the other a priest. The focus is on them, not a playboy billionaire, and Batman might as well be the ghost of Christmas past.

Which brings us to 2012 and The Dark Knight Rises—and a Batman who confronts the specters that haunt post-9/11 America with literal force. He can punch terrorists, solve the energy crisis with nuclear power, and buy up all the weapons in the world so they can never be used against us. He can drop out of the shadows at any moment and beat up the muggers and gangsters—and he can look awesome doing it.

Nolan’s Dark Knight portrays the best action movie Batman ever, and it’s a pretty clever action movie besides. But, from my perspective, the image of police heroically charging into armed protestors contrasts starkly with the reality of cops cracking the heads of unarmed and nonviolent demonstrators in various Occupy camps. Although I respect Nolan’s ability to paint in the medium of Batman, his Caped Crusader isn’t the one I want—even if the movie’s success shows that he’s riding today’s political winds.

Still, it’s just one Batman. The question of who’s the real Batman could be a Zen koan: Batman is Batman. It makes more sense to ask: Who’s your Batman?

Art Information

- "Pure West" © Rahzzah Murdock; used by permission

- "Batman and Gideon" © Hadley Langosy; used by permission

Andrew Vanden Bossche is TW’s Talking Geek columnist.

He’s also a powerful machine that accepts freelance work. Experience the Mammon-Machine at his website and on Twitter @mammonmachine.

"Designers still barely knew what games were when they made Metroid, and it shows. Yet as a kid, I responded to its cold and cavernous world, to those creepy aliens and blue caves, as art, not unlike the way a budding filmmaker might have been obsessed with Night of the Living Dead in the late 1960s and 1970s." — "Shouting Outside the Halls of Art"