TW Column by Steven Lewis

Can We Ever Meet A Parent’s Expectations?

During the summer of 1964, my exasperated father was explaining once again how the paper and pencils and flash cards that filled his small warehouse on Long Island would someday help children learn to read and write. A good life, he suggested with a Horatio Alger wave of a well-chewed cigar, was bound as if by heavy-duty strapping tape (Aisle 5) to the notion of purpose. He then pointedly flourished the burning ember at a rusty boxcar that I—his big-eared, bleary-eyed, eighteen-year-old son—was to spend the day unloading.

Compliant soul that I was at the time, I dared not explain that I had a different notion of my life’s purpose. So I kept my tongue to myself and proceeded to haul several tons of construction paper out of the hellishly hot boxcar and onto skids in the hellishly hot warehouse.

And, a month later, hightailed it far from New York and the wholesale school supplies business—all the way to the cooler climes of Madison, Wisconsin, where I decided, in between demonstrations against the war in Vietnam and fruitless attempts to gain one Helen Schellen’s attentions (no one had explained to me that my purpose in going to college was to attend class), that I was going to be a rich and famous writer. My purpose.

Back home after my first experience of being totally unprepared for finals (no one told me about them, either), I found my voice among the ruins of a C- average and stood up to the old man.

I argued that a good poem or story could save a person’s life. My father looked at the A in freshman English and the D’s in meteorology and sociology, gnawed some more on his panatela, muttered something about hell freezing over, and then demanded that, as long as he was paying my tuition, I must put some business courses in my curriculum. Utilizing a new language I had learned at the demonstrations that fall, I told him that I flatly rejected all capitalist labor rhetoric. He, in turn, mouthed some fascist-establishment language and told me I was a spoiled and self-indulgent brat.

So, somewhat like St. Francis standing up to his father, I walked out of my dad’s house. Unlike St. Francis, however, I did not shed the clothes he had bought for me. Nor did I give him back his car keys. I drove off in a huff to seek my own purpose as a world-renowned bard—and the eternally elusive affections of Helen Schellen.

Over the next few semesters, as I dated girls not named Helen and managed to raise my GPA to a solid C+, I actually began to find some small success with my writing. My father was not impressed with my first triumphant literary efforts, nor with the staple-bound magazines in which they appeared: Modine Gunch and Road Apple Review. He wanted microeconomics in the curriculum. I enrolled in Shakespeare and figured The Merchant of Venice would let me know everything I needed to know about filthy lucre. He demanded business writing. I registered for creative writing, explaining on the hall phone in the dorm that all writing was creative. He extolled the virtues of marketing principles. I took a course in Mark Twain.

And thus I continued to shadowbox with my father over the twin definitions of fame and purpose in life. I was not impressed that he continued to pay my tuition, and he, in turn, was not impressed with the publication of my first poetry chapbook by New Erections Press: “No, Father, it was not reviewed in the Times Book Review.” Nor did he appreciate my answer to his follow-up question about sales, even after I explained that it sold dozens of copies (two) and, all things being equal, paid me quite handsomely (a dozen contributor’s copies).

And, all things being sort of equal in my evolving, purposeless Ram Dass existence, by the time I hit my stride as an unemployed fifth-year junior, I tumbled into love (not with Helen Schellen). I got married. I soon had what amounts to my first adult conversation with my beautiful, sexy bride, as we discussed waiting until we were both out of college and gainfully employed before making a baby.

Five minutes later we were naked.

Fifteen minutes after that she was pregnant.

And thus it came to be that I, Sam Lewis’s starry-eyed goof-off of a boy, was soon to be someone’s dad.

Talk about self-induced cognitive dissonance. And with the old man’s harangues on purpose silently coursing through my veins like some latent genetic infection—it turns out that even extreme Midwestern cold cannot kill viruses—I slowly, over the course of that gestation, grew to fear in my wandering heart that seeking fame was indeed reserved for the spoiled and self-indulgent. And that, alas, there wasn’t a poem in the universe that could dig a ditch or perform an appendectomy or save a life or supply a child with the paper and pencils necessary to learn. Or pay the rent.

Or buy baby shoes.

Although I went on to pursue an MFA rather than that MBA (some dreams die hard), soon after graduation I found a tweed jacket with elbow patches and turned to teaching, the methadone clinic for writing addicts. As an educator, I figured I could at least make a living, still have some time to write, and never question whether my existence had purpose. And, yes, still be famous.

Yet, over the next 25 years, while I mentored several thousand writing students—and freelance writing actually became profitable—my father and I still disagreed about the hallmarks of a purposeful life. I would send him clippings of readings and book launches. He would occasionally remind me that with summers off and long Christmas vacations, my work wasn’t really work.

And, on those occasions, I sometimes wondered if the precious time I devoted to pounding on a keyboard could have been more purposefully spent doing something of greater value to humankind. Or making better money for my growing family.

I read and re-read (and taught) Marianne Moore’s damning pronouncement: “There are things that are important beyond all this fiddle.” I despaired that I’d ever write something as lovely as a tree. Or as functional as a warehouse.

Then, in 1999, like a post-modern deus ex machina, my editor at Dutton faxed me a front-page article she received from the Marion, Indiana, Chronicle-Tribune with the headline “Book Saves Man from Bullet Wound.”

My pulse quickened as I read about 27-year-old Shenandoah “Shane” Maxey, who was coming home from work one day when he heard a gunshot and suddenly felt a pain in his arm. “‘It felt like someone punched me really hard in the arm,” he said. Turns out that someone, perhaps his ex-wife, had shot at Mr. Maxey with a .22 caliber gun. But before the bullet had shattered bone or severed an artery, it struck and burrowed into a book Maxey was carrying in an insulated lunch bag he had slung over his shoulder. And not just any book…my book! Zen and the Art of Fatherhood.

“I was reading that book in hopes of becoming a better father,” Maxey was quoted as saying. ”Now I’m really glad I bought [it].”

Me, too. I was famous! I had purpose! I jumped in the truck and raced into town to mail my father a copy of the article, so he’d know that hell had frozen over. I also sent Mr. Maxey a new copy of the book to replace the one with the bullet hole.

Unfortunately, the old man wasn’t as impressed as I’d hoped. On the phone from Boca Raton, my 88-year-old dad chuckled at the story…and then wondered what the advance for the book was.

That was thirteen years ago. Since then, my father passed along to his ultimate reward, I published a few more books destined for the remainder table, and my children continued to add to my fortune of DNA with sixteen grandchildren.

Today, I have recently retired from a satisfying, if not lucrative or famed, career as a creative writing teacher (a sinecure, my father might have said). I am still writing, however, always writing. And yes, I’m still pondering why I do what I do, still wondering why I do it every day, even as I continue to question if all this fiddle does anyone any good. And perhaps because I’ve spent decades recommending to my students that they “write what you know” without ever knowing fame or fortune myself, I have recently become an enthusiastic advocate for “write what you don’t know.”

Which might be why I was thinking about Mr. Maxey today and wondering whatever happened to him. Did he become a better dad? Did his wife try to shoot him again? The cad never wrote to thank me for saving his life—or for the book I mailed him so many years ago.

As the Tralfamadorians said in Slaughterhouse-Five, so it goes. And for me it goes all the way down to this: It all seems pointless if I’m not writing about it.

Publishing Information

-

"Poetry" by Marianne Moore, The Norton Anthology of Poetry website, edited by James F. Knapp.

Art Information

- "Workers in Warehouse, 1915"; Engineering Department Photographic Negatives (Record Series 2613-07), Seattle Municipal Archives; Creative Commons license

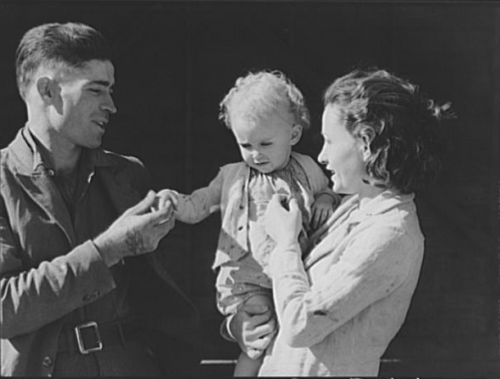

- "Farmer and Family, Hillview Cooperative, Osage Farms, Missouri," 1939; photograph by Arthur Rothstein for the U.S. Farm Security Administration; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

- "Young Man Lying in a Hammock," 1910; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Steven Lewis is a contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing.

Steven Lewis is a contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing.

"My work as a writer is to get myself back to the primitive wordless understanding of what it means to walk upon this earth." — "A Nature Writer Lets the Outside In"