Essay by Li Min Mo

Writing to Make Sorrow and Longing Tangible

Words have had great power over my life. Like memories, they formed part of my history.

At age three, I heard over and over again from my older sisters and my Ma that my dad had been executed.

Many decades later, I learned that my dad was one among countless political prisoners taken in 1949 by the Chinese Communist Party under Mao Zedong. Not one of those prisoners was given a proper burial, nor were their loved ones allowed to mourn. Execution was a big word; not being allowed to mourn would haunt me.

Many decades later, I learned that my dad was one among countless political prisoners taken in 1949 by the Chinese Communist Party under Mao Zedong. Not one of those prisoners was given a proper burial, nor were their loved ones allowed to mourn. Execution was a big word; not being allowed to mourn would haunt me.

I didn’t know a survivor had the responsibility to uncover the lies, the unmarked graves, the injustice that still exists among us.

Only after struggling with the vicissitudes of life for decades did I come to writing. I discovered grief has color and shape and texture. The choking horrors and the complexity of human upheavals could all become tangible by the act of writing. A writer could bring light to testimonies.

Before I found words, I was filled with a passion for shapes and their lines. My eyes were my pencil or brush.

I looked outside on a blustery winter morning and saw my mother making a fire, her back the perfect image of a pear shape. Her gold silk robe was worn, the intricately embroidered red flowers and green leaves split open, bits of silk padding sticking out.

Every morning after that, I looked out the window and sketched with my mind’s eye what was out there. My mother’s back was so comforting and powerful. With her right hand holding a palm fan, she was the fire maker and symbol of peace.

Another day, I saw a neighbor holding a chicken, its wings clipped back. She was preparing to slaughter the bird as a sacrifice for her deceased husband. A short, thin woman, she wore a thick dark-blue jacket; her back looked like a poorly wrapped package. The chicken’s dangling neck, on the verge of being slashed, was a sad curvature.

A soldier approached, his gun slung over his shoulder. Its metallic harshness was very much like the stiff, upright posture of the small man, his mouth twisted by threatening words: “No mourning, no sacrifice!!! That’s the order!!! No mourning!!”

I learned that although death was final, we weren’t allowed to mourn our losses. That order weighs on me to this day.

I learned that although death was final, we weren’t allowed to mourn our losses. That order weighs on me to this day.

Life came at me in furious fits and starts. Uprooted so many times, I was shocked by one strange neighborhood after another. I heard unfamiliar dialects. Not being able to make sense of my world silenced me.

I struggled with thoughts like tangled brambles: Where do I begin?

To sort out the mess, to attempt to make beauty shine in my squalor, I started painting when I was in third grade. Tempera paint, watercolors, crayons, and paper immediately became my trusted friends.

Once I learned how to read, great writers showed me what could be done with words. Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales took me to another world. When I was older, the tragedies spun by the Russian masters—Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Gorky—opened me and touched my soul.

Storymaking is a form of archeological uncovering, like shining a light in a dark cave and revealing the amazing paintings on the wall: wooly mammoths with tusks, large trunks, and grotesque expressions.

When I write, I find shards of my father, bits and pieces of the villages of my past, and the mysteries hidden in the bones of those who gave their lives for their beliefs. I connect with my ancestors and give shape to my memories, dreams, and visions.

I admire wordsmiths who can do somersaults and gymnastics with words, turn them into prose of layered thoughts, a complex mathematical diagram or origami: eight-pointed stars embedded inside five-pointed stars, folding within each other’s symmetry.

My thoughts are so much simpler: All I want is some kind of harmony. Writing makes me feel as though I’m making peace with that part of myself that’s so broken, so terrified, that’s been lost in the maze and thrown into the pit with poisonous snakes. I write to make allies of my adversaries.

This desire to write into the night, to be with the moon and the constellations, is something I’ve come to think of as the birthing of what was broken inside of me. Writing is weaving, making a crazy quilt, a receiving blanket for a newborn.

This is my way of mothering myself: This unscrambling of letters, this web-making in the dark, this spelling out of words, turning the sorrow and longing into something tangible, hoping it will bring with it a kind of joyful, dancing music.

Art Information

- “Mao Zedong announcing the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949″; public domain

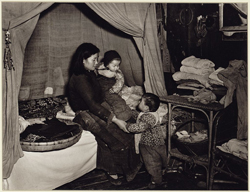

- “Mother with two young children in sleeping area of dwelling in the Kiangsu Province or Yunnan Province in China” by Arthur Rothstein; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

Born in Shanghai, Li Min Mo now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Under the name Li Mo, she is the author of a memoir, Spirit Bridges (Streetfeet Press, Boston, 2009). She's been a storyteller and artist for 30 years and recently retired as an adjunct professor at Lesley University.

Born in Shanghai, Li Min Mo now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Under the name Li Mo, she is the author of a memoir, Spirit Bridges (Streetfeet Press, Boston, 2009). She's been a storyteller and artist for 30 years and recently retired as an adjunct professor at Lesley University.

Learn more at Li Min Mo’s website.

“I had earned the nickname 'Monkey Girl' for my skill in scaling brick walls, bamboo polls, and tall trees. Animals crawled inside and outside of me."—"Freeing a Life at Chinese New Year"