TW Column by Judith A. Ross

Finding Artistic Order When Your Life Blows Up

Artists tend to thrive on routine. Their work is often the result of doggedly showing up day after day, immersing themselves in their ideas and techniques. But what happens to their creative flow when they face a massive crisis? How do they cope?

The recent work of painter and ceramicist Anne Francey offers insight into the artistic process under fire. This past summer, I went to the Hudson Valley in upstate New York to talk with her. I also took in a group exhibit of “Works on Paper” at the Carrie Haddad Gallery that included several of Francey’s pieces.

But I first saw her in a 2012 New York Times video series about her daughter, Suleika Jaouad. The Times column “Life, Interrupted” by Jaouad documents what it's like to be diagnosed at 22 with acute myeloid leukemia. During the first video, the camera suddenly focuses on Francey while Jaouad spoke to a nurse. Despair, fear, and exhaustion etched the mother’s face as she removed her glasses and rubbed her eyes.

Throughout her daughter’s three-year ordeal—which began in 2011 and included a bone marrow transplant, round after round of chemotherapy, and too many hospitalizations to count—Francey faced every parent’s worst fear.

As a junior in high school, I faced my worst fear at the time when I watched my mother get progressively sicker and then die of breast cancer. As a young mother of 39, I took my own year-long roller-coaster ride with the disease. I’m all too familiar with the life-churning “interruptions” that a cancer diagnosis brings for both a patient and her family. The thought that my sons might grow up with the same deep well of loss that I had was unimaginable.

And yet, that’s the lesson cancer teaches—that the impossible is possible.

The gallery in Hudson, New York, was full when I walked in, but I immediately spotted the Swiss-born Francey. At 59, she wore her light-brown hair in a short, spiky haircut that offset large, deeply lidded blue eyes. With her reedy proportions, the loose white top and slim black pants she had on that day echoed the content of her works on the walls.

A continuation of the “Seismographies” series she began several years ago, the pieces are poster-sized with white, often wispy, abstracted stems, seeds, and pods flung in an airy choreography across inky backgrounds. Her inspiration may come from nature, but it’s nature gone topsy-turvy. In “Untitled 9” (2015), for example, disembodied flower petals float through the air; those attached to stems dangle upside down, as other organic shapes hang in space.

The day after the opening, I visited Francey’s home studio in Saratoga Springs. The first piece I noticed hanging on a bright white wall was a multi-colored, kimono-shaped tapestry made up of ceramic rectangles the size of large postage stamps.

Called “Suleika’s Shield,” the piece has 368 tiles, Francey told me. She started it in the summer of 2011, when her daughter came home after her first rounds of chemotherapy. The shield—shown at the opening of this column—includes bird imagery and some literal messages. La coeur qui se saigne (the heart that bleeds), one tile notes in Francey’s native French.

“In art, you can hide things,” she says. “I couldn’t always discuss my fears. For her protection, I had to be even; I could not panic. I didn’t want her to worry about me.”

My conversation with Francey touched on not only her fear for her daughter but her need to find order through her work. She later emailed me journal notes she'd made about “Suleika’s Shield” while creating it, a process that took three years. “I play with the idea of magical protection,” she wrote at the time, “as each rectangular ceramic piece echoes a day within a turbulent period of time.”

Much of the art she made during those years was done in sections. She spent days and sometimes weeks away from her studio caring for her daughter. But the piecemeal process of creation also reflected her struggle with “the idea of trying to put things together, trying to make sense,” she says, “to keep yourself together.”

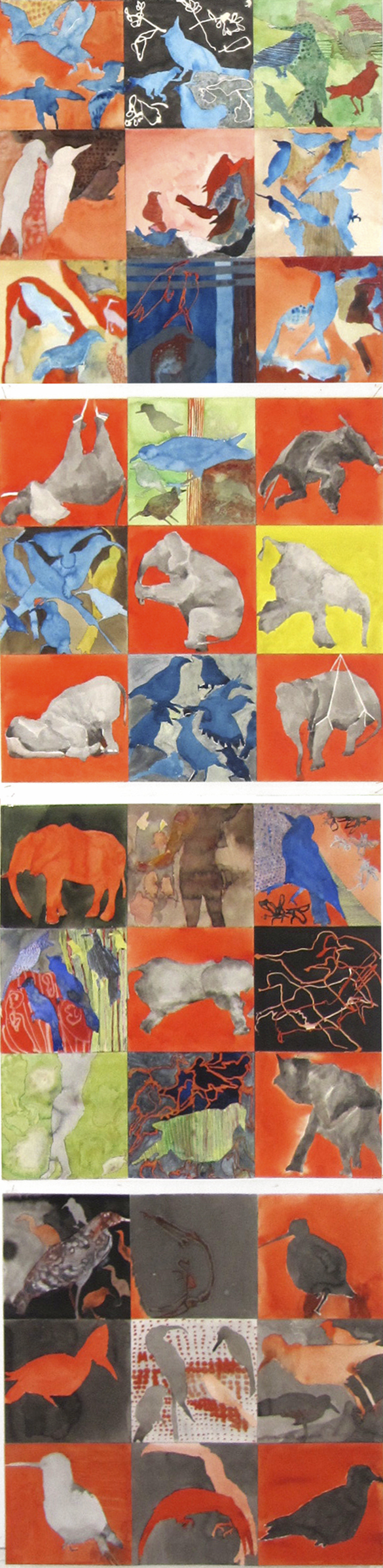

Another piece Francey developed during her daughter’s illness was a series of watercolors that began as a diary she could work on while away from her studio. The resulting “Cariatide de Papier,” a column of 36 panels that reflect as many weeks, was inspired by the caryatids of ancient Greece, sculpted female figures that often took the place of pillars or other architectural supports. The panels depict birds, both grounded and airborne, and elephants tethered or off balance in some way.

Birds, Francey says, became stand-ins for her own inner turbulence: “I call them les oiseaux dans tous leurs états (the birds in all their states). All these different states reflected my own state of mind, depending on what was going on with her.”

Emotions she didn’t dare express out loud or even admit to herself would appear at the end of her paintbrush. Pointing to one panel, she told me:

What I would produce would scare me. I didn’t like these guys; their beaks were too pointy. I couldn’t deal with the turmoil of what was going on, and then it would come out on the paper.

The elephants took shape when her daughter left the hospital after her bone marrow transplant. “I was exhausted,” Francey says. “So then it became more literal. These elephants were helping me think about strength, so that’s why they are all being challenged in their gravity, balance, and weight.”

With her daughter’s cancer in remission, Francey finally has both the time and emotional remove to step back and evaluate the work she created during the crisis. “The art meant to witness and record can be ‘good art’ of course,” she notes in a later email to me, “but it needs to have both form and content intrinsically linked to become so.” She adds:

That is why I feel more confident about the ceramic piece ‘Suleika’s Shield.’ Even though I was working on it all along, it took its final shape slowly, and I just finished it last year, when she finally started to feel better.

Since Francey hung the completed piece on her studio wall, her daughter has not returned to the hospital.“I know it’s just a coincidence that I call it a magic shield,” Francey says with a laugh.

I’m not so sure. A protective shield made by a mother’s loving hands surely must contain a few magical powers.

Publishing Information

- “Life, Interrupted: A Video Portrait of Cancer in Young Adulthood” by Tara Parker-Pope, New York Times, April 3, 2012.

- “Life, Interrupted” by Suleika Jaouad, ongong New York Times “Well” column.

- “Works on Paper” (group exhibit with Anne Francey), Carrie Haddad Gallery, August 26, 2015 – October 4, 2015.

- Anne Francey’s website.

Art Information

- “Suleika’s Shield” (2014), “Untitled 9” (2015), and “Cariatide de Papier” (2013) © Anne Francey; used with permission.

- Photograph of the artist with “Seismographies” by Hédi Jaouad; used with permission.

Judith A. Ross is a contributing writer at Talking Writing, where her “Talking Art” column appears regularly.

Judith also writes about climate change for Moms Clean Air Force and helps managers with their written communications. She blogs at Shifting Gears.