Theme Essay by Jeff Maehre

Really Virtual: What Does It Mean to Be Someone Else?

Ray Kurzweil, controversial futurist, predicts that soon people will achieve immortality by uploading their consciousnesses to hard drives and occupying synthetic bodies. From The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, here’s his vision of virtual reality circa 2030:

The Web will provide a panoply of virtual environments to explore…. We will be able to visit these virtual places and have any kind of interaction with other real, as well as simulated, people (of course, ultimately there won’t be a clear distinction between the two), ranging from business negotiations to sensual encounters."

These encounters will include the sights and sounds, even smells, of the environment. (“‘Virtual-reality environment designer’ will be a new job description,” writes Kurzweil.)

These encounters will include the sights and sounds, even smells, of the environment. (“‘Virtual-reality environment designer’ will be a new job description,” writes Kurzweil.)It’s easy to see the appeal of such entertainment—a souped-up version of Sims or Second Life, an opportunity to be in a virtual environment as opposed to seeing one on your computer screen. Combine this multi-sensory experience with a world in general in which those who can afford to will be able to select more enhancements to their bodies and appearance, genes will be manipulated with greater precision, we’ll interact with realistic humanoid robots, and reading a book will seem like making one’s own soap or playing the washboard.

I’ll sample many of these technologies when they appear. I’d like to immerse myself in a basketball arena, playing the role of a star in a championship game, and I’d like to play the role of an ancient Roman Emperor. (I’d need several essays to scratch the surface on the “sensual encounters” my filthy mind has already imagined.)

But I know the limitations. Yes, nanobots will flood my neurons with the sights and sounds of the arena—I’ll hear the screaming fans and see teammates grunting through their paces and even be able to dribble the ball and feel its weight in my hand. But what about the mental and emotional aspects? I won’t be feeling or thinking what it is to be a star athlete—the pressure, the emotional baggage from a past I’ll have no access to—I’ll be me, thinking, “Wow, this is neat, I’m pretending to be a basketball player, and I’ll be able to preserve the illusion until I have to actually do something with the ball.”

I’ll come away entertained, my senses nicely filled, an hour used well enough, but not having grown an awful lot as a person, except to the extent that I will think about what it is to enter these worlds and what their traits say about humans in our particular moment.

If I want to understand another person’s consciousness, I’ll have nothing available to me except for the hard wood of the washboard. I’ll turn to the ancient form that in the year 2011 we’ve already grown adept at marginalizing—literature. Through first-person narration, I’ll immerse myself in the language and thought patterns of a character. In any mode used by a good writer, I’ll see deep into the characters’ minds, entering their encounters, able to anticipate hurts or joys—in a sense, going into a scene as the character.

Charles Baxter’s story “Talk Show” presents the consciousness of a five-year-old boy. Here’s a particularly breathtaking excerpt:

In bed he counts his fingers. His parents are not awake. Somehow it comes out to eleven. He tries again. Ten this time. Once more. And again the sum comes out to eleven. He holds his hands up in the semidark, silhouetting them against his Swiss-chalet nightlight. He twists his hands to the right and left. He curls and uncurls his fingers. Where is the extra finger?"

By putting the fingers right in front of us—how can we not picture our own flesh backlit, hanging above the covers?—Baxter is placing us where we need to be to relive the conundrums of childhood, to feel the poignancy of the project, inventorying our own bodies, perplexed but ultimately safe in bed and intuiting somehow that no matter how many fingers we have they are ours to twist and curl.

Of course we’re interacting with Baxter as much as we are the character here—pulling from the page not just his observations and sentiments, but his unique way of puzzling these into comprehensible language. He has done his work and it allows us to do ours. It’s something that dwellers of today’s virtual words enjoy, too. They like to reverse-engineer the created environment in order to understand the developer’s assumptions and predilections. But these environments provide far less fodder than the printed page.

I’m not predicting that a world full of virtual playgrounds will spur such a need for a different kind of consciousness-jumping that the novel will once again be king. But because the concept of inhabiting another’s consciousness will almost certainly be one of the most discussed cultural phenomena in the coming decades, people will be reminded of literature’s value. At the very least, the art form won’t see its very existence threatened.

I’m not predicting that a world full of virtual playgrounds will spur such a need for a different kind of consciousness-jumping that the novel will once again be king. But because the concept of inhabiting another’s consciousness will almost certainly be one of the most discussed cultural phenomena in the coming decades, people will be reminded of literature’s value. At the very least, the art form won’t see its very existence threatened.Some pockets of society will probably react strongly against technological advances that question what it is to be human. With their neighbors having dishes washed by cyborgs and attending church virtually, they may bust out the sewing machine for a homemade dress or buy a dusty turntable from the thrift store and find some vinyl to spin on it—anything to preserve the analog world. This includes paperback books creased and marked up by a previous owner, read on a real blanket on real sand.

But I think reading culture’s best avenue to something a notch above mere survival is in doing what other media can’t. Literature needs to fill its own niche as doggedly as possible rather than trying to compete where it can’t. Books that read like movies are miserable, and chick-lit novels with sitcom episodes labeled as chapters trivialize reading and writing.

Writers aren’t going to bring a scene to life in more detail than a virtual reality environment does—a lover of language may enjoy a written account of it more than a trip into VR, but we won’t make it more vivid. We won’t entertain more with a horse race scene than the various souped-up media of the future will.

But we can succeed in the revelation of a person’s consciousness. We can make readers really feel what it is to step into someone else’s skin.

We can do this if we stand up to editors who tell us no one values interiority anymore—if we have faith that there are smart and patient readers out there somewhere—if we believe in literature.

Publishing Information:

- The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology by Raymond Kurzweil (Viking, 2005).

- Through the Safety Net: Stories by Charles Baxter (Viking, 1985).

He likes robots but hates people who act like them.

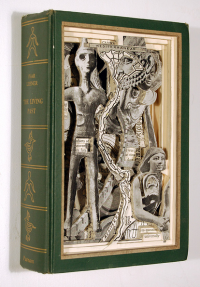

Artist

Brian Dettmer is originally from Chicago, where he studied at Columbia College. He currently lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia. His work has been exhibited and collected throughout the United States, Mexico, and Europe. He has had solo shows in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Miami, and Atlanta. He is currently represented by a number of galleries, including Packer Schopf in Chicago and Toomey Tourell in San Francisco.

Brian Dettmer is originally from Chicago, where he studied at Columbia College. He currently lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia. His work has been exhibited and collected throughout the United States, Mexico, and Europe. He has had solo shows in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Miami, and Atlanta. He is currently represented by a number of galleries, including Packer Schopf in Chicago and Toomey Tourell in San Francisco.

Dettmer’s work has gained international acclaim through Internet bloggers and traditional media. His bibliography includes the New York Times, Modern Painters, Wired Magazine, Vogue Italia, Harper’s, and National Public Radio. Visit the website of Brian Dettmer for more information.

Two Dettmer images of altered books appear with this article: "A World on the Wane," 2006, 8-1/2" x 6" x 1-5/8", courtesy of the artist and Packer Schopf Gallery; and "The Living Past," 2007, 8-3/8" x 5-3/4" x 1-7/8", courtesy of the artist and Toomey Tourell Fine Art.