TW Essay by Richard Hoffman

For William Orem

Not long ago, I saw either my death, the very shape of it, or else the dark outline of my fear. Maybe they're one and the same. I can’t read a flouroscope, but when I craned my neck from my fetal position on the icy metal table and saw a black shape among the billowy, barium-illumined folds of my insides, a jagged twist of fear shot through my chest, and my heart began to pound.

Over and over, I told myself the dark form, something like a footprint, was no doubt a normal shadow, but my fear remained. I tried to read the looks, the gestures, the rhythms of the technician and his assistant. Surely if they had seen my death in there, hiding like a rat, they would betray their fear or pity somehow. But they were busy, the technician reassuring me with his practiced patter—“just a few more moments, you’re doing fine, you’re doing fine”—and his assistant chirpy as a real estate agent. Impenetrable, their behavior was no easier to read than the round screen where I’d seen the murky tread of my mortality.

What if I’d been less inhibited? What if I’d cried out, “Jesus, what the hell is that?” What would they have answered? I wish I hadn’t looked, but how could I not?

After I dressed, I was served juice and crackers. I wanted to ask—of course I did—but the technician preempted that and, frankly, I was a little relieved. "Your doctor will be in touch with you when he's interpreted the results."

Driving home, stopped at a red light, I noted that I’d already begun talking to myself in the stoic’s voice I’ve used occasionally when faced with a loved one’s frightening hospital stay or at a bedside vigil when death was inescapable. Death is a normal shadow, I told myself; I’ve just trained myself, like the rest of us, to ignore it.

I began to wonder at how much of what we call our daily lives is perhaps a vast conspiracy in which we all take part, a contract we have with one another to play our various roles, all to distract us from that dark shape, to keep us sheltered from what I'd glimpsed—inside me!—and was still trying to absorb.

In addition to the stoical view, but not occluding or softening it, was another, more spiritual perspective. It sounds trite to call it a lesson in humility, but that’s what it was. I was tiny and soft, a mealworm or a slug, a dust mote, a random speck of nearly nothing.

The stoic again took the upper hand: If there was a fight ahead, I told myself, I would try to be worthy of it; if resignation was called for, I would try to accept my sentence with dignity.

But soon I found I was accusing myself of having wasted time, of squandering what life I'd been vouchsafed, now that it might be nearly over. Was that because I hadn’t sufficiently valued it? Because I didn’t know how best to live it? Because I’d somehow transgressed? Such are the self-flagellations of a cradle Catholic. And I suspect my insistence on some level of personal responsibility was an assertion of my own authority: I must have caused it; I am a sinner. But it's all right, the thinking goes, because we are all sinners and, being human, all we can do is ask forgiveness.

I didn't ask forgiveness, though. I just appreciated the elegant psychological slipknot I'd executed, a metaphysical maneuver I now saw clearly, feeling thankful to those who taught me how to do it. Our need to at least feel in control of what is beyond control requires us to blame ourselves for nearly everything that befalls us. But the universality of that predicament excuses us, too, so long as we acknowledge it and are willing to be judged as "only human" and forgiven. It was hardly an accident I'd employed this half-hitch and loop when I felt most vulnerable, tiny, and inconsequential.

I was lost in these metacognitive musings, successfully in flight from my fear, when the light changed, and, impatient, the guy behind me leaned on his horn, slamming me back in my body and scaring the living crap out of me.

I wasn't worried about what my body would do with this intruder lurking in my bowels; my body would fight as it had been trained to do by eons of evoluton. It would either win or lose against its opponent. It knew what to do, and I would make sure it had the best medical allies in that contest.

No, my mind would be the arena in which I had to fight, where defeat would mean despair and meaninglessness and misery. I began to see that my parents and teachers, my culture and religious training, had afforded me multiple perspectives, taught me to plead my case for meaning on multiple grounds, to embrace various premises, as if I'd been given a wide shelf of books to take down and read from as needed. The books didn't need to agree; they only needed to suffice for the moment. I felt grateful for this insulation from terror and madness. I felt well-equipped.

I still think it's odd, though, that in the days after, waiting for my test results, not once, not for a single moment, did I entertain the idea of an afterlife. I remained plenty scared, though hiding it from others helped me put it from my mind for hours at a time. I considered my absence and its impact on my wife, my grown children, friends, colleagues, students. I thought of work I wanted to accomplish. I thought of things I needed to do and people I needed to speak to while I still had the chance.

I started making lists: people to forgive, people to ask for forgiveness, people to thank. I even thought about what I would like done with my remains. The prospect of a waiting paradise or a terrible punishment never crossed my mind, however; no other world awaited me, I felt sure.

But this world, finite, was never more real to me than it was that week—those seven days, those ten thousand minutes or so—awaiting the phone call from my doctor. It's hard to recapture, now that my anxiety has eased, that weird penumbra fear had bestowed on even the most familiar things.

"Even though it's uncomfortable," the doctor said, "it's a good thing to repeat the procedure every few years." I thanked him and told him I agreed.

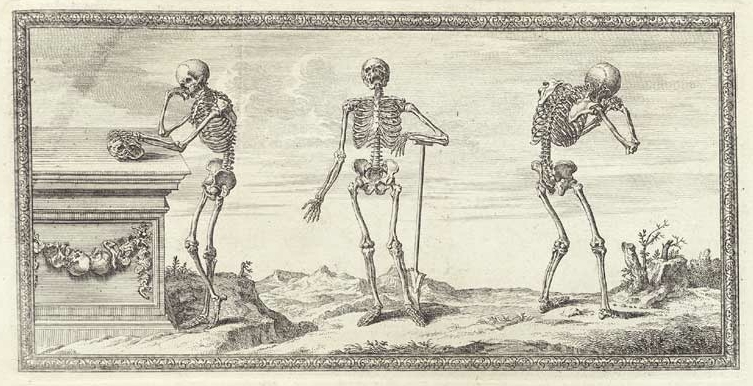

Art Information

- Skeleton drawing from Osteographia by William Cheselden (1733); public domain.

Richard Hoffman is author, most recently, of the memoir Love and Fury, which was a finalist for the 2014 New England Book Award from the New England Independent Booksellers Association. He is also author of the celebrated Half the House: A Memoir, reissued in a new twentieth anniversary edition in 2015, with an introduction by Louise DeSalvo.

Richard Hoffman is author, most recently, of the memoir Love and Fury, which was a finalist for the 2014 New England Book Award from the New England Independent Booksellers Association. He is also author of the celebrated Half the House: A Memoir, reissued in a new twentieth anniversary edition in 2015, with an introduction by Louise DeSalvo.

He's the author of three poetry collections: Without Paradise, Gold Star Road (winner of the 2006 Barrow Street Press Poetry Prize and the 2008 Sheila Motton Award from the New England Poetry Club), and Emblem. He's a fiction writer as well; his Interference and Other Stories was published in 2009.

A past chair of PEN New England, Hoffman is senior writer in residence at Emerson College in Boston.

He joined TW editor Martha Nichols for the panel "Long vs. Short: Nonfiction Storytelling in the Digital Age" at the AWP 2015 conference in Minneapolis.